The Decline of Scottish Common Sense Realism (Part Five)

Friday, August 17, 2018 at 12:16PM

Friday, August 17, 2018 at 12:16PM The Decline of SCSR

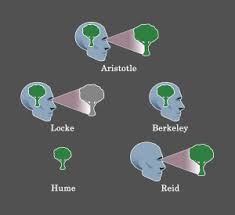

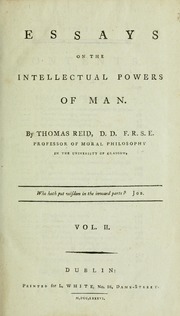

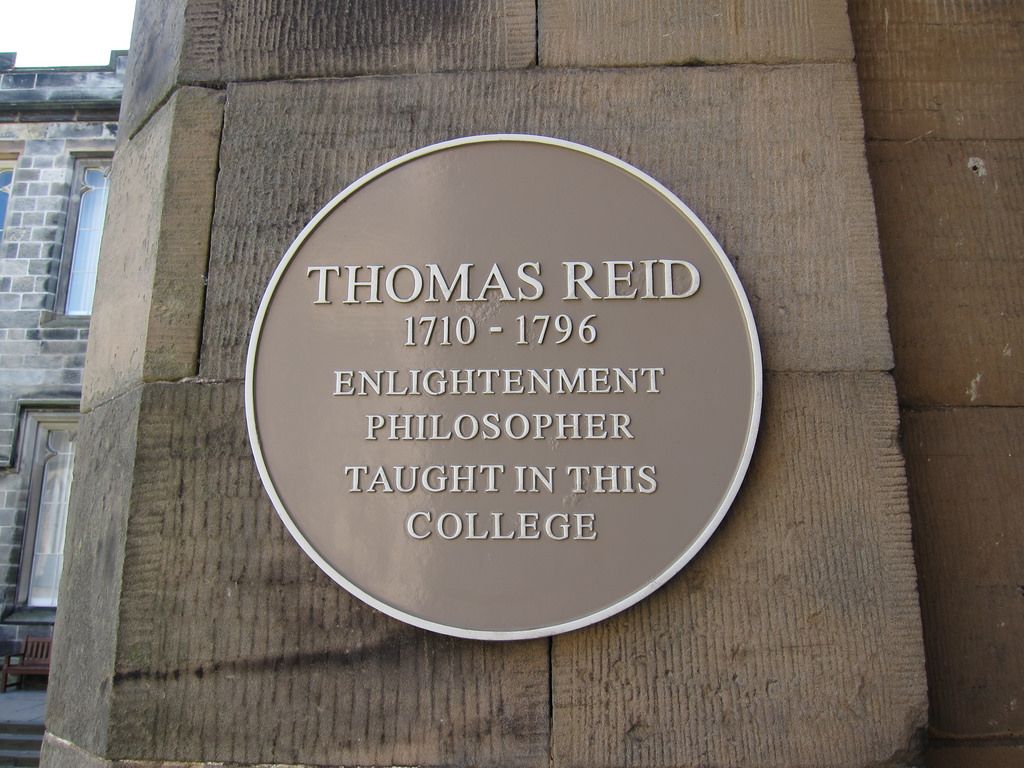

Although more influential during his lifetime than was Hume, one question lurking throughout this discussion is why did Reid and SCSR fall into such relative obscurity so quickly if common sense is self-evident? The obvious reason is that Reid’s Inquiry was completely overshadowed soon after its publication by Immanuel Kant’s ground-breaking Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Reid’s philosophy of common sense (along with the Scottish school associated with him), was openly maligned by Kant, who did not read English. Kant curtly labeled “common sense philosophy” as mere opinion. It did not help that the notoriously poor translation of Reid’s work Kant had read erroneously translated “common sense” as “public rumor” (Robinson, How Is Nature Possible, 120, n. 6).

Kant dismissed any attempt to establish a rigorous systematic philosophy based upon the opinions of the unlearned masses utilizing something as crude as public rumor (i.e., public opinion). Common sense had much in common, Kant noted, with the Popularphilosophie, as it was then known and taught in Germany. Kant, who claimed to be troubled by his personal mania for systematizing, expressed open disdain for the popular philosophy then in vogue. Kant was a vocal champion of the so-called Schulphilosophie (the philosophy of the schools–i.e., that of professional philosophers). Kant complained that a philosophy like SCSR could be used by any “wind-bag” to confound even the most sophisticated philosopher–a point which actually works in Reid’s favor! Kant’s criticism of SCSR boils down to the fact that common sense is not sophisticated, too simplistic, and amounts to nothing but a “herd mentality.” This is a charge which has been repeated often by critics of SCSR since the days of Reid. No doubt, such a back-handed dismissal by someone as influential as Kant pushed Reid and SCSR deep into philosophical backwater.

But as recent Kant scholarship has convincingly shown (i.e., Manfred Kuehn, Karl Ameriks, Daniel Robinson), Kant’s negative assessment of SCSR widely misses the mark. Several of Kant’s proposals were actually quite similar to those previously advocated by Reid. Many of Kant’s German contemporaries were greatly influenced by the Scottish philosophy and Reid in particular. When pressed to explain how it was that the a priori categories of his “transcendental idealism” were necessary to explain human sense perception, Kant defaulted to “Mutterwitz,” i.e., to “mother nature” (Kant, Critique, A133-5/B172-4)–a notion virtually identical to that of Reid, who spoke of his first principles as coming from the “mint of nature,” i.e., from God who made us with such capacities At the end of the day, Kant, quite ironically, ends up where Reid begins–we must utilize a priori categories because we are made this way. But Kant has no explanation for “mother wit,” while Reid does.

Reid scholars have catalogued additional reasons for the diminished impact of SCSR after Reid’s death. These include the fact that Reid’s philosophy came under withering attack from a significant English philosopher who came to prominence two generations later, John Stuart Mill (1806-1873). Mill was the chief proponent of utilitarianism, which held that moral philosophy must give due consideration to the “greater good” for individuals and society, and as such cannot be grounded in moral first principles as Reid insisted. Mill complained that Reid’s appeal to intuition was just another way of promoting self-interest, not the common good.

Yet, another reason suggested for SCSR’s decline is that the compiler of Reid’s Works, Sir William Hamilton, ham-fistedly attempted to merge his own Kantian affinities with Reid’s SCSR, a matter compounded by the fact that Hamilton was not anywhere near the capable spokesman for SCSR that Reid was. Finally, some have noted the Scottish Enlightenment simply had run its course, especially when Scottish Universities began to hire non-Reidian professors more inclined to utilitarianism, or the Continental philosophies of Kant and Hegel. Wolterstorff attributes this, in part, to the rise of Hegel’s imprint upon modern philosophical development which left Reid behind under a wave of continental rationalists, British empiricists (Wolterstorff defends the notion that Reid was neither) and the Kantian-Hegelian synthesis (Wolterstorff, Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology, x).

Yet, another reason suggested for SCSR’s decline is that the compiler of Reid’s Works, Sir William Hamilton, ham-fistedly attempted to merge his own Kantian affinities with Reid’s SCSR, a matter compounded by the fact that Hamilton was not anywhere near the capable spokesman for SCSR that Reid was. Finally, some have noted the Scottish Enlightenment simply had run its course, especially when Scottish Universities began to hire non-Reidian professors more inclined to utilitarianism, or the Continental philosophies of Kant and Hegel. Wolterstorff attributes this, in part, to the rise of Hegel’s imprint upon modern philosophical development which left Reid behind under a wave of continental rationalists, British empiricists (Wolterstorff defends the notion that Reid was neither) and the Kantian-Hegelian synthesis (Wolterstorff, Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology, x).

No doubt, the chief reason for the decline of Reid’s prior wide influence was the triumph of Kant’s “transcendental idealism” over Reid’s “common sense.”

The Resurgence of Reid and Common Sense