Note: An updated version of this essay, appears here: https://www.kimriddlebarger.com/thomas-reid-1?rq=reid

Who Was Thomas Reid and Why Does His “Common Sense” Philosophy Still Matter?

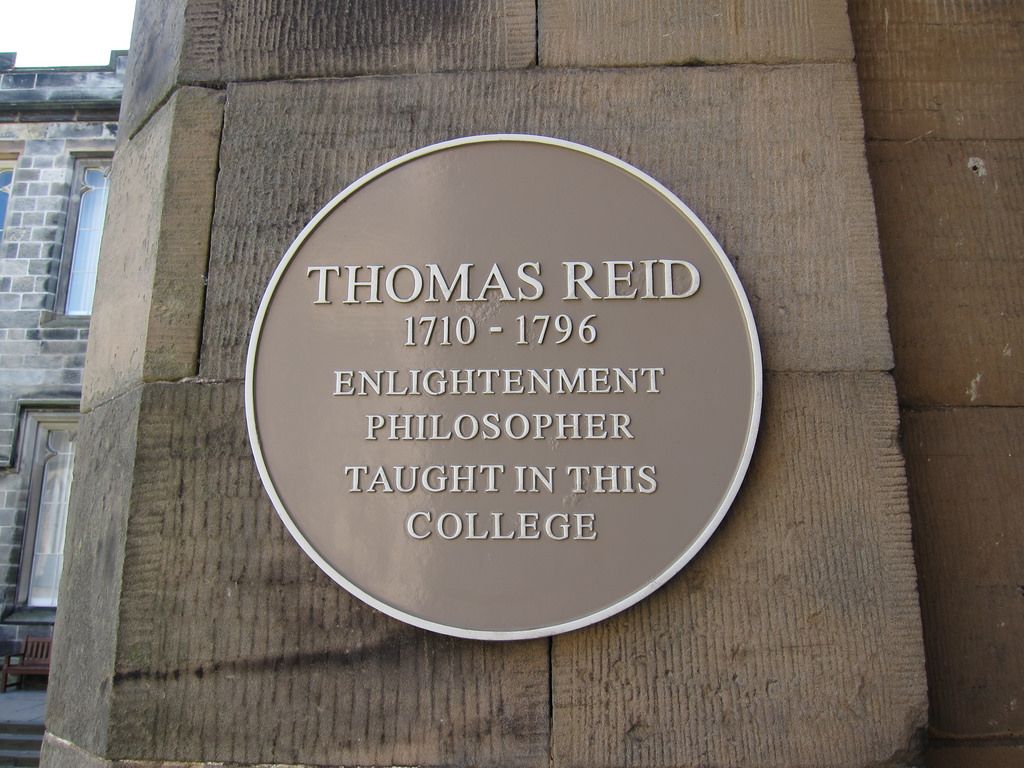

Reid's Official PortraitThomas Reid (April 10, 1710 – October 7, 1796) is best known as the founder and principal philosopher of “common sense,” or more properly, “Scottish Common Sense Realism” (SCSR). Reid was highly respected and quite influential in the days of the eighteenth century Scottish Enlightenment, but the popularity of Reid and his common sense philosophy quickly faded in subsequent generations. Although destined for relative obscurity, Reid’s influence did remain strong in several quarters. Of late, there has been a Reidian resurgence of sorts, reflected in several volumes about Reid’s philosophy, the publication of a new critical edition of his works (by the University of Edinburgh), and through favorable treatment by so-called “Reformed Epistemologists,” Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff.

Reid's Official PortraitThomas Reid (April 10, 1710 – October 7, 1796) is best known as the founder and principal philosopher of “common sense,” or more properly, “Scottish Common Sense Realism” (SCSR). Reid was highly respected and quite influential in the days of the eighteenth century Scottish Enlightenment, but the popularity of Reid and his common sense philosophy quickly faded in subsequent generations. Although destined for relative obscurity, Reid’s influence did remain strong in several quarters. Of late, there has been a Reidian resurgence of sorts, reflected in several volumes about Reid’s philosophy, the publication of a new critical edition of his works (by the University of Edinburgh), and through favorable treatment by so-called “Reformed Epistemologists,” Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff.

The purpose of this essay is to introduce Thomas Reid’s philosophy of “common sense,” which, I believe, has been far too long misunderstood and therefore neglected, and which still has an important role to play in formulating a “common sense” apologetic for the Christian religion–an apologetic which centers in the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ as Christianity’s chief truth claim.

The Life and Times of Thomas Reid

Reid was born and raised in Strachan, near Aberdeen, Scotland. The son of a Church of Scotland minister (the Rev. Lewis Reid, 1676-1762), Reid’s mother was Margaret Gregory, one of twenty-nine children, and from the famed Gregory clan. Her first cousin, James Gregory (1638–1675), was a respected mathematician and astronomer who invented the reflecting telescope. Reid began attending Marischal College in Aberdeen in 1723, and graduated Master in 1726. Reid was only 16, but this was typical for the time. Reid was greatly influenced by his teacher, George Turnbull. Turnbull was a follower of idealist philosopher Bishop George Berkeley–Reid later came to oppose the Bishop with great vigor, as he did the empiricist philosophers John Locke and David Hume. During his time at Marischal, Reid became thoroughly acquainted with Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathmatica, and showed much appreciation for Newton throughout the course of his career.

Before becoming a philosopher, Reid served as a parish minister. He was licensed to preach by the Church of Scotland in 1731, and briefly pursued theological studies after licensure. In 1737, Reid was ordained and took a pastoral call to a small church in New Machar (near Aberdeen). While in New Machar (1740) Reid married his wife, Elizabeth. Together they had nine children–eight of whom, sadly, Reid outlived. Little is known about Reid’s ministry in New Machar, but the story circulates that he was not near as popular in the parish as was his wife. This was due to rumors that Reid was given his call through patronage–an unpopular practice in small, rural parishes like New Machar.

It is likely that Reid belonged to the “moderate party” of Hugh Blair (a popular Scottish minister). The so-called “Moderates” focused on Christian morality, not the Calvinistic doctrines found in the Westminster Standards, to which all ministers of the Church of Scotland were required give to affirmation. Reid’s sermons are lost to us, but his deep personal faith and piety is expressed in a prayer in which he praised God for his providential mercy after Elizabeth had been spared during a serious illness.

While in New Machar, Reid continued to read and study philosophy, specifically the work of Glasgow moral philosopher Francis Hutcheson and his influential book, Inquiry into the Origins of the Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. Reid also read and digested fellow Scot David Hume’s Treatise on Human Nature (1738-40). Reid’s first publication, an essay On Quantity, was published for the Royal Society in October of 1748. This is a good indication that philosophical interests–not theological matters–were driving Reid’s intellectual life even while serving in the parish.

In 1751, Reid took a professorship at King’s College Aberdeen, becoming a teacher, lecturer and regent. In accepting this call, Reid was required to give up his ordination and did so in 1752. Along with John Gregory and other notable intellectuals, Reid founded the Aberdeen Philosophical Society (popularly known as the “Wise Club”), which continued meeting until 1773. During this time, Reid completed his doctoral work, but did not publish his first book until 1764, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, when Reid had reached the age of 54. As was the case with Immanuel Kant, who claimed to be awakened from his “dogmatic slumbers” after reading a German translation of David Hume’s Treatise, Reid too was stirred by Hume–in Reid’s case by Hume’s An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, first published in 1748. Hume’s published works were a continual source of discussion within the Wise Club, and Reid’s Inquiry is thought to be largely based upon lectures developed for Wise Club discussions.

In 1751, Reid took a professorship at King’s College Aberdeen, becoming a teacher, lecturer and regent. In accepting this call, Reid was required to give up his ordination and did so in 1752. Along with John Gregory and other notable intellectuals, Reid founded the Aberdeen Philosophical Society (popularly known as the “Wise Club”), which continued meeting until 1773. During this time, Reid completed his doctoral work, but did not publish his first book until 1764, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, when Reid had reached the age of 54. As was the case with Immanuel Kant, who claimed to be awakened from his “dogmatic slumbers” after reading a German translation of David Hume’s Treatise, Reid too was stirred by Hume–in Reid’s case by Hume’s An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, first published in 1748. Hume’s published works were a continual source of discussion within the Wise Club, and Reid’s Inquiry is thought to be largely based upon lectures developed for Wise Club discussions.

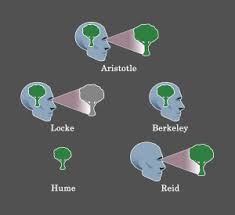

David HumeReid’s Inquiry was primarily a response to Hume, but Reid also took aim at other advocates of the so-called “ideal theory.” According to Reid, in addition to Hume, those who held the “ideal theory” included Rene Decartes, John Locke, and George Berkeley. Ideal theorists placed the mind and our ideas between sensation of the external world and our knowledge of it. Ideal theorists were necessarily skeptical of the even the possibility of direct knowledge of the external world–although they never expressed their skepticism as boldly as the logic of their theories dictated. Reid, who quickly became Hume’s most powerful critic, sought to challenge what Reid identified as the “monster of skepticism” given life by Hume. If anything characterizes Reid’s philosophical work, it is his fierce opposition to all forms of epistemological skepticism typified by his Inquiry. Reid’s challenge to the ideal theorist still stands. Can your philosophy actually assure us of the existence of the external world? Or does the author (however unintentionally) ultimately drive us to skepticism by placing a representational or mental “theory of ideas” between the world which exists and our perception of it.

David HumeReid’s Inquiry was primarily a response to Hume, but Reid also took aim at other advocates of the so-called “ideal theory.” According to Reid, in addition to Hume, those who held the “ideal theory” included Rene Decartes, John Locke, and George Berkeley. Ideal theorists placed the mind and our ideas between sensation of the external world and our knowledge of it. Ideal theorists were necessarily skeptical of the even the possibility of direct knowledge of the external world–although they never expressed their skepticism as boldly as the logic of their theories dictated. Reid, who quickly became Hume’s most powerful critic, sought to challenge what Reid identified as the “monster of skepticism” given life by Hume. If anything characterizes Reid’s philosophical work, it is his fierce opposition to all forms of epistemological skepticism typified by his Inquiry. Reid’s challenge to the ideal theorist still stands. Can your philosophy actually assure us of the existence of the external world? Or does the author (however unintentionally) ultimately drive us to skepticism by placing a representational or mental “theory of ideas” between the world which exists and our perception of it.

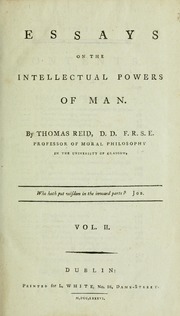

Shortly before Reid’s Inquiry was published, he was offered the prestigious Professorship of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where he became the immediate successor to Adam Smith (1723-1790), the author of the influential Wealth of Nations (1776). Reid accepted this call and remained at Glasgow until his retirement in 1781. Productive in his retirement, Reid turned his university lectures into the books, Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (1785) and Essays on the Active Powers of the Human Mind (1788).

In these volumes on intellectual and active (and agentic) powers, Reid defends a libertarian notion of human freedom–i.e., that human agency is responsible for free actions of men and women, who are morally accountable for their choices. But Reid thought his view perfectly compatible with the Westminster Standards which prescribes the agency, but not the causality of human action in light of the mystery of “the predestination and foreknowledge of God in conjunction with the liberty of man” (Reid, "Prescience and Liberty," in Works of, II.977).

Reid also directly attacked Hume’s notion of personal identity, in which Hume famously held that human identity is nothing but the on-going memory of our experiences over time. Hume once wondered whether he still existed while he slept, and if his existence was reconstituted each morning upon awakening. Reid appreciated Hume’s wit, but held that any sequence of memories we may have is grossly insufficient to ground personal identity and self-awareness, which are common sense beliefs held by all–even by those like Hume, though the latter candidly admitted to doubting them.

One of Reid’s most effective methods of criticism of his opponents was to argue that philosophers like Hume often raised provocative questions in the safety of their private studies, boldly going against widely accepted “common sense” human convictions of the day (i.e., causality and on-going personal identity). As Reid pointed out, such men cannot live out their philosophical convictions in the real world they actually inhabit. Reid playfully jabbed Hume, stating that if he (Reid) chooses not to believe my senses, “I break my nose against a post that comes in my way, I step into a dirty kennel; and after twenty such wise and rational actions I am taken up and clapped into a madhouse” (Reid, Inquiry, in Works of, 1:184). Hume may question whether there is a third thing (causality) between the billiard ball and cue which strikes it, but presumably such skepticism never stopped Hume from playing billiards. Hume’s theory does not stop us (nor Hume) from trusting our senses.

By all accounts, Reid was a modest and humble man, well-liked, and widely respected. His obituary (in the Glasgow Courier) describes his as “a life distinguished by an ardent love of truth, an assiduous pursuit of it in various sciences, by the most amiable simplicity in manners, gentleness of temper, strength of affection, candour, and liberality of expression.”

Reid on “First Principles”

The great conundrum faced by philosophers since time immemorial is the question “how do we know what we know?” This question falls under the sub-category of philosophy known as epistemology. Those who contend that all human knowledge arises through our senses are called “empiricists.” Those who believe that our knowledge is grounded in our ideas (i.e. our mental powers and state of mind) are often identified as “idealists.”

Enter the much better known contemporary of Reid, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1722-1804), whose volume Critique of Pure Reason, was first published in 1781. What made Kant’s philosophy so important and ground-breaking was that Kant made a compelling case that while all knowledge begins with sense perception–the data received via our senses–the knowing process does not end there. Without the mind having the innate ability to act upon these sensations so as to transform them into knowledge, the world would remain unintelligible to us despite the data coming from our senses. Kant believed that there are specific mental categories which owe nothing to experience, and which are hard-wired into us which shape those sensations we do receive.

These so-called a priori categories (i.e., they are in place before we experience the world) include notions of time and space, logic, and mathematics. A creature without such categories would have the same sensations and see the same appearances we do, but would have an entirely different experience of them. My dog and I see the same tree. Since he does not have the mental categories I have, we experience the same tree quite differently. According to Kant, we see not “the thing in itself,” but only the thing as interpreted by our minds according to the a priori categories. This is reflected in Kant’s well-known distinction between the noumenal (the world beyond experience but which can reasonably be inferred from experience) and the phenomenal (the world which is actually experienced and accessed through the senses).

Reid, it has been said, worked backward from Hume’s skepticism to ask, “what would be necessary” if we are to know the world as it is? Reid wonders “what capacities must the human mind possess in order to truly know the external world?” He classifies these capacities as “first principles” which he believes are grounded in the so-called “common sense” of humanity. These principles are simply assumed and cannot be proven. We utilize them without any prior reflection upon them, nor can we “prove” them, because to do so we must utilize the very capabilities we are trying to prove. Although people universally reason from these first principles even if they do not believe in God, whenever we seek to get behind “common sense” to discover why things are the way they are, Reid argues there is no way to explain the existence of these first principles and the common sense of humanity apart from God who created the world and has designed us to live and act within that world. Reid writes,

I thank the Author of my being, who bestowed it upon me before the eyes of my reason were opened, and still bestows it upon me, to be my guide where reason leaves me in the dark. And now I yield to the direction of my senses, not from instinct only, but from confidence and trust in a faithful and beneficent Monitor, grounded upon the experience of his paternal care and goodness. In all this, I deal with the Author of my being, no otherwise than I thought it reasonable to deal with my parents and tutors. I believed by instinct whatever they told me, long before I had the idea of a lie, or thought of the possibility of their deceiving me (Reid, Inquiry, in Works of, I.184).

The theistic implications of Reid’s first principles ought not be overlooked. We reason via common sense because our Creator has designed us to do so.

Immanuel KantSince Kant too was awakened through his interactions with Hume, we should not be surprised that both Reid and Kant were chasing the same goal. Reid wanted to challenge Hume’s skepticism, as did Kant–albeit Kant’s method of doing so was quite different than Reid’s. Reid appealed to those things assumed by all humans in all ages and across all cultures–identifying those first principles which ground human knowledge in the real world–and in not mere experience or in mental categories. This makes Reid a “common sense realist”–we do indeed apprehend the world as it is through ordinary daily activity. Reid really ought not be classified as a pure empiricist, although he does fit within the empiricist camp. Kant, on the other hand, thought the best way to do this was to define the limits of human reason by identifying those a priori mental categories which transform mere appearances of things into our knowledge of them. Kant’s so-called “transcendental idealism” sets out the premise that knowledge begins when we receive appearances of external things via sense perception, but we cannot regard these appearances as objects of knowledge until our minds organize these appearances through a set of fixed a priori categories already present in the mind.

Immanuel KantSince Kant too was awakened through his interactions with Hume, we should not be surprised that both Reid and Kant were chasing the same goal. Reid wanted to challenge Hume’s skepticism, as did Kant–albeit Kant’s method of doing so was quite different than Reid’s. Reid appealed to those things assumed by all humans in all ages and across all cultures–identifying those first principles which ground human knowledge in the real world–and in not mere experience or in mental categories. This makes Reid a “common sense realist”–we do indeed apprehend the world as it is through ordinary daily activity. Reid really ought not be classified as a pure empiricist, although he does fit within the empiricist camp. Kant, on the other hand, thought the best way to do this was to define the limits of human reason by identifying those a priori mental categories which transform mere appearances of things into our knowledge of them. Kant’s so-called “transcendental idealism” sets out the premise that knowledge begins when we receive appearances of external things via sense perception, but we cannot regard these appearances as objects of knowledge until our minds organize these appearances through a set of fixed a priori categories already present in the mind.

The critical issue with which Reid and Kant were wrestling is that we all have to start the knowing process somewhere. But where, exactly? We must assume certain things to be true and already in place in our minds from our earliest years of self-consciousness and prior to experience of the world, otherwise our sensations would remain just that–mere sensations and never pass into knowledge.

Reid identified two types of first principles–necessary (certain) and contingent (probable) which provide the a priori framework to necessary understand the external world (Reid, Intellectual Powers, in Works of, 1:435). Those first principles Reid identified as “necessary” (i.e., it is impossible to deny them) include logic (i.e., the law of non-contradiction) certain rules of grammar, mathematics, morals (unjust actions cause harm) and metaphysical realities–what we perceive actually exists. Reid is certain that God would never allow an evil demon to deceive us as Descartes once wondered. Reid also believed that whatever exists has a cause–in direct opposition to Hume’s skepticism about accepting things as “true” which he could not actually observe.

Those first principles which Reid identified as “contingent” include things such as consciousness of our own person (self-awareness), knowledge of the external world, that what I remember really did happen, that my personal identity truly exists as far back as I can remember, and that those things which I see and perceive really do exist. Reid also argued that we have power as human agents to determine our own actions (we learn about causality, through our own agentic powers, as when infants, we strike the mobile above our heads which causes it to move), that we are able to tell truth from error, we know that other minds exist, and that human testimony is ordinarily true unless we have good reasons to believe otherwise. Reid added that the future course of the world will be similar to what it has been in the past.

Reid was clear as to the importance he placed upon such first principles.

All reasoning must be from first principles, and for first principles no other reason can be given but this, that, by the constitution of our nature, we are under a necessity of assenting to them. Such principles are part of our constitution, no less than the power of thinking: reason can neither make nor destroy them; nor can it do anything without them. . . . A mathematician cannot prove the truth of his axioms, nor can he prove anything unless he takes them for granted. We cannot prove the existence of our minds, nor even of our thoughts and sensations. A historian, or a witness, can prove nothing unless it be taken for granted that the memory and senses may be trusted (Reid, Inquiry, in Works of, 1:130).

To deny these principles, Reid thinks, is absurd.

We must start the knowing process by assuming certain capacities are in place whether we can prove this or not. Reid begins with first principles, both necessary and contingent. Kant, on the other hand, rejects Reid’s realism, instead contending that we cannot see things as they really are, only our perceptions of them mediated through his famous “categories.”

Reid on “Common Sense”

For Reid, first principles and common sense are closely related. In Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man, Reid writes, “first principles, principles of common sense, common notions, [or] self-evident truths” are “no sooner understood than they are believed. The judgment follows the apprehension of them necessarily, and both are equally the work of nature, and the result of our original powers” (Reid, Intellectual Powers, in Works of, 1:452). Previously, Reid identified common sense as “necessary to all men for their being and preservation, and therefore it is unconditionally given to all men by the Author of Nature” (Reid, Intellectual Powers, in Works of, 1:412).

More specifically, common sense refers to “the consent of ages and nations, of the learned and unlearned, [which] ought to have great authority with regard to first principles, where every man is a competent judge” (Reid, Intellectual Powers, in Works of, 1:464). Such principles are identified as common sense because they are common to humanity and held by all people across time and cultures. Reid grounds his belief in common sense in an empirically justified generalization that this is the necessary state of affairs for humans to know anything–especially that the external world exists. To put it simply; this is “common sense” because it is demonstrably common to all of humanity. If all people see an object, and then universally assign the same qualities to that object, without any prior explanation or self-reflection required before doing so, this can only because their knowledge of that object is “true.” All people instinctively think this way, unless convinced to doubt this knowledge by teachers of the ideal theory.

While Reid argued common sense was virtually self-evident because universal (in this regard, Reid is a foundationalist of a sort), his critics then and now, attacked him at this very point by claiming his common sense philosophy was nothing more than an appeal to majority opinion–the “wisdom of the vulgar.” If true, this chips away at the very idea of the supposed universality of Reid’s first principles. If common sense is really nothing but popular opinion verified by counting noses, and by observing how the uneducated rabble make decisions, then such first principles amount to nothing of value in settling truth claims. No philosopher worthy of the name would dare make such an appeal.  But Reid anticipated this line of criticism and as a good Newtonian, made clear that his first principles were actually empirical and psychological observations, reflecting the way people actually think and interact with the world around them. To give this point some teeth, at several places, Reid appeals to universal elements in the structure of human language (anticipating the later work of G. E. Moore and J. L. Austin). Reid points out that all human language is built upon a distinction between the active and passive voice, and that all languages distinguish between the qualities of things, and the things themselves. This goes a long way toward making Reid’s point.

But Reid anticipated this line of criticism and as a good Newtonian, made clear that his first principles were actually empirical and psychological observations, reflecting the way people actually think and interact with the world around them. To give this point some teeth, at several places, Reid appeals to universal elements in the structure of human language (anticipating the later work of G. E. Moore and J. L. Austin). Reid points out that all human language is built upon a distinction between the active and passive voice, and that all languages distinguish between the qualities of things, and the things themselves. This goes a long way toward making Reid’s point.

To put it another way, Reid’s first principles are not true because most people accept them. Nor are they true because this is how the common man or woman expresses themselves when asked about how they know what they know. Rather, people think and interact with the world as they do, precisely because this is how their creator has made them to think and act. Reid, to my knowledge does not refer to the “divine image” while discussing these common sense capabilities–although he does speak of the divine image in humanity when discussing moral liberty, and conscience (Reid, Active Powers of Man, in Works of, II.564, 585, 615). But are not the abilities given us by our creator something akin to humans reflecting the image of their creator? We are born with the capacity to utilize these first principles without any self-reflection, or without being able to give any reasons for doing so. This is how God made us, and is his way of enabling and equipping his creatures to live in the world which he has made.

Reid on “Perception”

Kant argued that what we perceive with our senses is not “the thing in itself,” since sense data must be mediated through our a priori categories. We all may see the same object which exists independently of our minds. Yet, our experience of that object is mediated through our a priori categories, determining the outcome of our sensations. If I cannot be sure that what I and others see is the same thing, even if we are looking at the same object, does this not lead to some form of skepticism despite Kant’s objections to the contrary?

Kant argued that what we perceive with our senses is not “the thing in itself,” since sense data must be mediated through our a priori categories. We all may see the same object which exists independently of our minds. Yet, our experience of that object is mediated through our a priori categories, determining the outcome of our sensations. If I cannot be sure that what I and others see is the same thing, even if we are looking at the same object, does this not lead to some form of skepticism despite Kant’s objections to the contrary?

Our understanding of perception is especially important to keep in mind when thinking about the contemporary debate over apologetic method between “evidentialists” (who make appeal to “facts” of Christianity as objective and “true”) and “presuppositionalists,” (who believe that our a priori categories, in this case, belief in the God of the Bible, are all-determinative to the knowing process, so that it is something like a fool’s errand to attempt to argue for the truth of Christianity merely using facts). According to presuppositionalists, the best way to defend the faith is assume the truth of Christianity and challenge unbelievers on grounds of inconsistency, factual error, and personal prejudices.

The founder of the modern school of presuppositionalism, Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) of Westminster Theological Seminary was “categorical” (pun intended) in his rejection of Kant’s absolute idealism and the latter’s distinction between noumenal and phenomenal realms (Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology, 103-115). But Van Til was greatly influenced by two Dutch Reformed theologians of an earlier generation, Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) and Herman Bavinck (1854-1921), both of whom utilized Kant’s a priori categories to explain how it is that we as fallen humans prejudicially (and sinfully) interpret the world around us–especially in light of the biblical data regarding the damage done to the human intellect and will by Adam’s fall into sin.

The traditional Reformed understanding of the effects of human sinfulness (including the so-called noetic effects of sin), when set forth through a priori categories such as Kant's, provided the ground for Abraham Kuyper to contend that the Fall completely effects the knowing process–so much so that Christians and non-Christians (through differing sets of a priori categories–one regenerate and one unregenerate) can properly be described as engaging in two kinds of science (note: you can insert any other human discipline here). There is a regenerate way of pursuing science, grounded in regenerate a priori categories, and there is an unregenerate way of doing science, grounded in sinful a priori categories. In this scheme, the gap between the way a Christian thinks and a non-Christian thinks amounts to a chasm. Van Til agreed and went so far as to state, “to the extent that the two systems of interpretation are self consistently expressed it will be an all-out global war between them” (Van Til, “Introduction” in Warfield, Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, 24).

This is also reflected in Van Til’s oft-repeated comments to the effect that it is useless to appeal to common ground or “common notions” upon which Christians (regenerate) and non-Christians (unregenerate) can both agree. God tells us (through Scripture) what things truly are and what they actually mean. In sense, this is where the discussion begins and ends for a regenerate person with regenerate a priori categories–they think God’s thoughts after him, while non-Christians cannot. This is why, according to Van Tilians, Christians should never appeal to non-Christians on the basis of facts supposedly held in common, when there cannot be any such thing. Instead, Christians apologetics ought to challenge non-Christian presuppositions while making the case that the world cannot make sense apart from Christian presuppositions and regenerate a priories. Christians and non-Christians will see the facts around them very differently (i.e., those things which occur in ordinary history in the external world in which we live) As Van Til puts it, “the only `proof’ of the Christian position is that unless its truth is presupposed there is no possibility of proving anything at all. The actual state of affairs as preached by Christianity is the necessary foundation of `proof’ itself” (Van Til, My Credo, 21).

If true, this would be a vindication of Kant and present a serious challenge to Reid’s notion of first principles and common sense which make appeal not to regeneration and a priori categories, but to first principles and common sense which are universally held in common by believer and unbeliever alike even after Adam's fall. Here, we see the fundamental divide between two approaches to Christian apologetics within Reformed circles, evidentialism and presuppositionalism. There is good reason why someone like B. B. Warfield was thoroughly perplexed by Kuyper’s instance on two kinds of science (one regenerate, one not), along with with Kuyper’s and Bavinck’s depreciation of Christian evidences, such as Jesus’ resurrection, which make appeal to knowable and verifiable events of history (Warfield, “Review” of Bavinck’s De Zekherheid des Geloofs, 117). Warfield followed Reid, while Kuyper, Bavinck, and Van Til, followed Kant.

For Van Til, there can be no such thing as a “brute fact,” or “uninterpreted" fact. Van Til expressed great reservation about Reid’s view of perception in relation to facts. “In the case of Scottish Realism there is, to say the least, an undue emphasis given to the attempt to establish a realism or independence of the object over against the subject” (Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology, 132). In making this comment, Van Til openly sided with Kant over Reid.

But Van Til seems to be of two minds when it comes to Kant’s handling of "facts." While rejecting Kant’s system, Van Til clearly embraced Kant’s understanding of how we experience and know the external world–the subjective a priori categories are all-determinative. Van Til claims Kant’s “Copernican Revolution” provides “a fully consistent presentation of one system of interpretation over against the other. For the first time in history the stage is set for a head-on collision” (Van Til, “Introduction” Warfield, Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, 24). If Kant is right about the necessity of a priori categories determining the meaning of sensations coming from the external world, then facts and their interpretation are indeed one thing. With this notion, Van Til is in full agreement. What a Christian sees as evidence for Jesus’ resurrection, a non-Christian may see as evidence of a mythological tale invented by Jesus’ followers.

Perhaps talk show host-psychologist Dr. Phil provides a helpful illustration when he quips “perception is reality.” Dr. Phil says this of someone who is obviously misinterpreting and distorting reality. Exposing such is presumably the reason why such a person is a guest on his program in the first place. Dr. Phil has every hope, it seems, of convincing the troubled person that their misguided perception is not reality. If such perceptions are indeed ultimate, there would be no possibility of any further useful discussion. The only remaining option to provide any relief would be the prescribing of medication.

The very possibility of exposing ill-conceived perceptions is one hint that Van Til’s notion of facts and their interpretation being one is not so air-tight after all. What if Reid is right about how we perceive the world and that we must assume certain things to be true to even talk about the matter of how and why common sense works? Reality grounds perception–or ought to. For Reid, what is presupposed is not the entire content of the Christian faith, nor even the authority of Scripture–as it is for Van Til. What is presupposed by Reid is that all people think in a common way, and are able to do so because God made them with the ability to do so. Reid’s focus is on epistemological method grounded in human nature, not a priori categories or prior mental content.

So what does this have to do facts and their interpretation? To my knowledge, Reid never addressed this matter as we are doing here. Reid is not doing Christian apologetics, rather, he’s refuting Hume and writing before Kant. But I do think Reid would be very comfortable affirming that within the context of human life, certain things are “self-evident.” But facts are “self-evident” because they occur in a context–not as “brute facts.”

An analogy might be useful to flesh this point out a bit further. Consider the matter of interpreting facts as like attending a play. Suppose you were to walk in mid-play, say during act 7, scene 2. You witness a character speak, and then make an insulting gesture to another character. You then immediately walk out of the play. Even though you heard the words spoken and witnessed the gesture, you would have no idea of what the words or gesture means, nor why they were important to the story. No "brute facts" here.

But things are quite different if you watch the entire play. To get some context, before attending the play you might read several reviews, and you may even have done some research on the playwright. You also know in advance that some play-goers will interpret the characters or the story line differently than the playwright intended. But the play–specifically act 7, scene 2–would make much more sense to you, once you who know who the character is, and why his insult figures so prominently in the plot line of the larger story. You understand that you cannot infallibly interpret the play by reading the playwright’s notes, nor can you possibly understand why every character was present during particular scenes, or why they were given the particular lines they were. Yet, you would not need to do so, nor would you ever expect to do so, to enjoy the play which unfolds scene by scene, one scene building upon another. When you watch the play in its entirely, you can figure out what was going on, because you now have the context to understand what you saw in act 7, scene 2. So it is with facts–they always occur in a context.

This context is what Reid’s notion of common sense provides us. Facts never occur in isolation from other facts. There is always a context for our experience of the external world. In the case of Christ’s resurrection–the critical fact for any discussion of Christian apologetics–the context (i.e., the story line of the play) is the Old Testament’s prediction of the resurrection of the body at the end of the age, the Psalmist’s prophecy that the coming Messiah would not see decay, that his kingdom was everlasting, followed by Jesus’ appeal to the sign of Jonah when speaking on several occasions about how he would fulfill the predictions just mentioned.

Those Jews and the Romans who opposed Jesus’ messianic claims certainly were not regenerate (at least not yet for some of them), but they understood full well what Jesus’ resurrection meant, even if they never came to faith in Jesus and even if they denied that the resurrection ever happened. Granted, the Jews and Romans had vastly different presuppositions and interpretations of the resurrected Jesus than did Jesus’ followers post-resurrection. But the resurrection still stands as the supreme fact of Christianity. Rejection of Jesus’ resurrection as confirmation of his claims does not mean his resurrection never occurred. There was still an empty tomb, and Jesus continued to appear to his followers. The rejection of Jesus by unbelievers stemmed from sinful and willful prejudice (whether self-conscious or not)–what Paul describes as the suppression of truth in unrighteousness (Romans 1:18).

In this instance, we see the critical difference between Reid and Kant and how their differing understanding of perception impacts how we interpret “facts.” How do we perceive the world around us? Directly and spontaneously? Or is our perception of the world ultimately determined by our a priori mental categories? Or even through our sinful presuppositions? Reid, Kant, and Van Til offer quite different answers to these vexing questions.

The Decline of SCSR

Although more influential during his lifetime than was Hume, one question lurking throughout this discussion is why did Reid and SCSR fall into such relative obscurity so quickly if common sense is self-evident? The obvious reason is that Reid’s Inquiry was completely overshadowed soon after its publication by Immanuel Kant’s ground-breaking Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Reid’s philosophy of common sense (along with the Scottish school associated with him), was openly maligned by Kant, who did not read English. Kant curtly labeled “common sense philosophy” as mere opinion. It did not help that the notoriously poor translation of Reid’s work Kant had read erroneously translated “common sense” as “public rumor” (Robinson, How Is Nature Possible, 120, n. 6).

Kant dismissed any attempt to establish a rigorous systematic philosophy based upon the opinions of the unlearned masses utilizing something as crude as public rumor (i.e., public opinion). Common sense had much in common, Kant noted, with the Popularphilosophie, as it was then known and taught in Germany. Kant, who claimed to be troubled by his personal mania for systematizing, expressed open disdain for the popular philosophy then in vogue. Kant was a vocal champion of the so-called Schulphilosophie (the philosophy of the schools–i.e., that of professional philosophers). Kant complained that a philosophy like SCSR could be used by any “wind-bag” to confound even the most sophisticated philosopher–a point which actually works in Reid’s favor! Kant’s criticism of SCSR boils down to the fact that common sense is not sophisticated, too simplistic, and amounts to nothing but a “herd mentality.” This is a charge which has been repeated often by critics of SCSR since the days of Reid. No doubt, such a back-handed dismissal by someone as influential as Kant pushed Reid and SCSR deep into philosophical backwater.

But as recent Kant scholarship has convincingly shown (i.e., Manfred Kuehn, Karl Ameriks, Daniel Robinson), Kant’s negative assessment of SCSR widely misses the mark. Several of Kant’s proposals were actually quite similar to those previously advocated by Reid. Many of Kant’s German contemporaries were greatly influenced by the Scottish philosophy and Reid in particular. When pressed to explain how it was that the a priori categories of his “transcendental idealism” were necessary to explain human sense perception, Kant defaulted to “Mutterwitz,” i.e., to “mother nature” (Kant, Critique, A133-5/B172-4)–a notion virtually identical to that of Reid, who spoke of his first principles as coming from the “mint of nature,” i.e., from God who made us with such capacities At the end of the day, Kant, quite ironically, ends up where Reid begins–we must utilize a priori categories because we are made this way. But Kant has no explanation for “mother wit,” while Reid does.

Reid scholars have catalogued additional reasons for the diminished impact of SCSR after Reid’s death. These include the fact that Reid’s philosophy came under withering attack from a significant English philosopher who came to prominence two generations later, John Stuart Mill (1806-1873). Mill was the chief proponent of utilitarianism, which held that moral philosophy must give due consideration to the “greater good” for individuals and society, and as such cannot be grounded in moral first principles as Reid insisted. Mill complained that Reid’s appeal to intuition was just another way of promoting self-interest, not the common good.

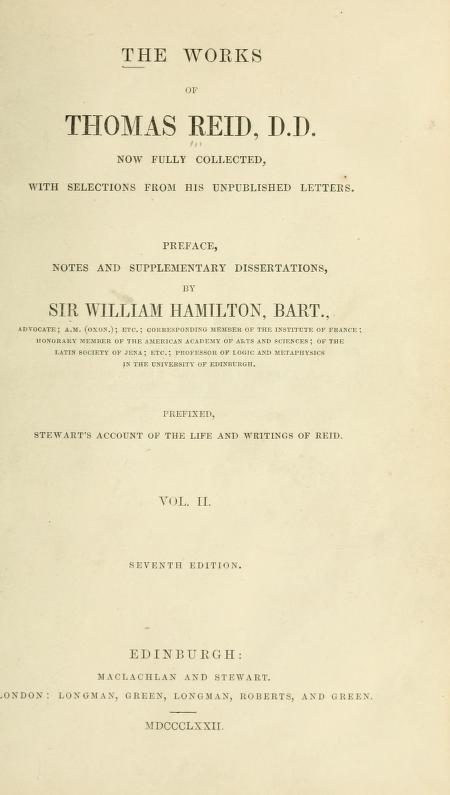

Yet, another reason suggested for SCSR’s decline is that the compiler of Reid’s Works, Sir William Hamilton, ham-fistedly attempted to merge his own Kantian affinities with Reid’s SCSR, a matter compounded by the fact that Hamilton was not anywhere near the capable spokesman for SCSR that Reid was. Finally, some have noted the Scottish Enlightenment simply had run its course, especially when Scottish Universities began to hire non-Reidian professors more inclined to utilitarianism, or the Continental philosophies of Kant and Hegel. Wolterstorff attributes this, in part, to the rise of Hegel’s imprint upon modern philosophical development which left Reid behind under a wave of continental rationalists, British empiricists (Wolterstorff defends the notion that Reid was neither) and the Kantian-Hegelian synthesis (Wolterstorff, Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology, x).

Yet, another reason suggested for SCSR’s decline is that the compiler of Reid’s Works, Sir William Hamilton, ham-fistedly attempted to merge his own Kantian affinities with Reid’s SCSR, a matter compounded by the fact that Hamilton was not anywhere near the capable spokesman for SCSR that Reid was. Finally, some have noted the Scottish Enlightenment simply had run its course, especially when Scottish Universities began to hire non-Reidian professors more inclined to utilitarianism, or the Continental philosophies of Kant and Hegel. Wolterstorff attributes this, in part, to the rise of Hegel’s imprint upon modern philosophical development which left Reid behind under a wave of continental rationalists, British empiricists (Wolterstorff defends the notion that Reid was neither) and the Kantian-Hegelian synthesis (Wolterstorff, Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology, x).

No doubt, the chief reason for the decline of Reid’s prior wide influence was the triumph of Kant’s “transcendental idealism” over Reid’s “common sense.”

Reid’s On-Going Influence and Resurgence

Reid and SCSR may have been relegated to the philosophical backwater by Kant’s Critique, but Reid’s influence never entirely abated, especially in America, where Reid was widely read and greatly appreciated. Thomas Jefferson was glowing in his praise for Dugald Stewart, the Scottish philosopher who did much to popularize Reid and SCSR throughout the English-speaking world. Several early United States Supreme Court cases make appeal to the “eminent Dr. Reid” when wrestling with the nature of facts and their interpretation. Scottish-American philosopher and president of Princeton College, James McCosh (1811-1894) and Yale professor and president Noah Porter (1811-1892) maintained strong interest in Reid and SCSR since both were concerned about the “objectivity of truth,” especially in matters of moral philosophy.

Since Kant’s and Hegel’s philosophical systems never became mainstream in America (with several notable exceptions such as Josiah Royce), it was the uniquely American school of philosophy, Pragmatism, which ultimately displaced Reid’s SCSR in America. Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914), the father of American pragmatism, agreed with Reid to a point, and argued that a universal common sense (as expressed by Reid) was worth recovering as a philosophical category, although Pierce thought common sense should be tied to experimental verification and the scientific method in the evolutionary sense of unfolding truth, and not grounded in first principles.

Following Pierce, the emerging pragmatists understood that outcomes in philosophy and the sciences were directly tied to verifiable consequences, most notably experiential “cash value.” William James (1842-1910), perhaps America’s most notable pragmatist, gave a well-received lecture on “Pragmatism and Common Sense” (James, Pragmatism, 63-75). James argued that common sense was compatible with pragmatism because James believed that without any prior self-reflection on such matters people naturally tended to gravitate toward ideas and systems of thought which produced concrete results. Since pragmatism is grounded in outcomes, there was little interest in anything like Reid’s first principles among the pragmatists. Pragmatism may make appeal to “common sense,” but such an appeal is actually a negation of common sense as understood by Reid. Yet, it was an easy intellectual move for Americans to give up SCSR for pragmatism, the nouveau cutting edge philosophy of the day.

Reid’s common sense was popularized on the Continent by French philosopher Victor Cousin (1792-1867) and was begrudgingly praised by Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900), a moral philosopher in the utilitarian tradition and the Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. G. E. Moore (1873-1958) one of the founders of the analytic tradition, cites Reid throughout his works. Reid’s work also had a significant influence upon American philosopher Roderick Chisholm (1916-1999) who trained a number of leading American philosophers, and who acknowledged that his own defense of common sense was indebted to Reid. More than one philosopher (i.e., Lehrer, Wolterstorff) has noted that in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, Wittgenstein is addressing what he calls “our shared world picture” in a manner strikingly similar to Reid’s “common sense” but without making appeal to our nature (first principles).

Perhaps those who have done the most to rescue Reid from the irrelevance of the philosophical backwater, are the so-called “Reformed Epistemologists,” Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff. Along with philosopher William Alston, they done much to rekindle current interest in Reid and SCSR, especially within the broader Reformed tradition. Reformed epistemologists contend that belief in God is “properly basic.” That is, it is rational to believe in God without any evidence or proof for doing so. According to Plantinga, religious belief is grounded in what John Calvin identified as an innate human awareness of God’s existence (the so-called sensus divinitatis).

Looking for philosophical antecedents, Reformed Epistemologists make appeal to Reid’s notion that beliefs arise in us spontaneously because we are born with them. These basic beliefs function like “common sense”–people believe in God without any prior reflection–but such simple belief can be further cultivated through instruction and maturation through the experiences of life. We may not be able to give a reason for God’s existence, and any reasons we might offer to prove God’s existence, presuppose the very capability of reasoning with which we have been created by God. For the Reformed Epistemologist, belief in God as properly basic functions as a first principle. Such belief is rational (and therefore “warranted”) every bit as much as are our belief in the existence of other minds, or our memory of past events.

Reformed Critics of Reid

When I mention Thomas Reid in the course of teaching apologetics, or in connection with the philosophical influences of SCSR upon Old Princeton (and the principal theologians who taught there–Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield), many people admit that they have never heard of Reid, or know very little about him. This is not surprising–given Reid’s unfortunate obscurity. Others in conservative and confessional Reformed circles have a quite negative impression of Reid, describing his philosophy as “rationalistic” or as a species of Thomism. These responses are an indication that the party is not very familiar with Reid’s philosophy, has not read Reid, nor understands him correctly–not a surprise given the bad press Reid often gets. Reid, as we have seen, is not a rationalist, anything but. With the recent re-discovery of Reid among Reformed Epistemologists, Roman Catholic defenders of Thomism have sought to distance themselves from Reid’s epistemology, seeing his “common sense” formulation as incompatible with the foundationalism of St. Thomas (Russman, “Reformed Epistemology,” in Thomstic Papers IV, ed., Kennedy, 200). Much of this criticism of Reid and SCSR comes from the camp of the followers of Cornelius Van Til, who contend that Reid’s philosophy lay behind B. B. Warfield’s unwitting compromise of the defense of the faith through Old Princeton’s advocacy of an apologetic method naively grounded in Christian evidences. Van Tilians are quite correct right to connect Warfield to Reid and SCSR (with certain modifications in the direction of Reformed orthodoxy made by Warfield). Yet, they regard Warfield’s approach as necessarily entailing an appeal to “right reason” which, to their minds, is an impossibility in light of the damage done to humanity (and to our a priori categories and interpretive abilities) as a consequence of the fall. Unregenerate people cannot utilize reason “rightly.” Warfield, supposedly concedes too much to unbelieving thought–a self-defeating move.

Much of this criticism of Reid and SCSR comes from the camp of the followers of Cornelius Van Til, who contend that Reid’s philosophy lay behind B. B. Warfield’s unwitting compromise of the defense of the faith through Old Princeton’s advocacy of an apologetic method naively grounded in Christian evidences. Van Tilians are quite correct right to connect Warfield to Reid and SCSR (with certain modifications in the direction of Reformed orthodoxy made by Warfield). Yet, they regard Warfield’s approach as necessarily entailing an appeal to “right reason” which, to their minds, is an impossibility in light of the damage done to humanity (and to our a priori categories and interpretive abilities) as a consequence of the fall. Unregenerate people cannot utilize reason “rightly.” Warfield, supposedly concedes too much to unbelieving thought–a self-defeating move.

To make the case that Van Til’s call for a correction of Old Princeton’s apologetic was necessary, Van Tilians often embrace the critical scholarly consensus (Ernest Sandeen, Jack Rogers, Donald McKim, and John C. Vander Stelt) which concludes that Warfield was a rationalist of sorts who departed from the biblicism of Calvin, even echoing the ill-founded critical observation that Warfield’s endorsement of "right reason" amounts to an implicit exaltation of human reason over divine revelation.

But Warfield’s comments about right reason fully comport with the way in which the Reformed orthodox of prior generations (i.e., Turretin) spoke of an “ministerial use” of reason which was necessary to interpret the revelation which God gives, while at the same time rejecting a “magisterial” use of reason which determines the content of revelation (Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 1: Prolegomena to Theology, 243). Warfield’s appeal to right reason amounts to nothing more than the proper utilization of those rational powers given us from birth by our Creator. To use “right reason” rightly, we must operate within an epistemological framework like that set out by Reid. Christians can make appeal to those evidences given by God through divine revelation, i.e., our Lord’s resurrection and self-attestation to be the very Son of God, because the Apostles did. The Christian evidences marshaled by Warfield for Christ’s resurrection have their origin in God’s revelation, not in human reason.

Reid, Old Princeton, and Warfield are also sharply criticized by American church historians Mark Noll and George Marsden, who both follow the critical and Van Tilian party lines in assuming that Reid’s SCSR has rationalist tendencies which, they contend, are incompatible with Reformed orthodoxy (Riddlebarger, Lion of Princeton, 247-253). Marsden contends that SCSR was simply not up to the challenge raised by Darwinians regarding what it was exactly that was entailed by primitive common sense beliefs (Marsden, “The Collapse of American Evangelical Academia,” in Plantinga and Wolterstorff, eds., Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God, 244). Because Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield failed to realized this, Marsden and Noll conclude Old Princeton’s apologetic was severely, if unintentionally, handicapped by their failure to more closely follow Calvin and his true theological heirs, Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck–both of whom B. B. Warfield highly regarded, yet openly criticized for abandoning apologetics altogether.

Recovering Reid’s Common Sense Epistemology–the Implications for Doing Apologetics

I hope that the points which follow will serve to place Reid, and by implication, Old Princeton, in a more objective and favorable light, and as a consequence, help Reformed Christians recover confidence in the proper use of Christian evidences when engaging in the apologetic enterprise.

First, Reid was a Christian philosopher whose necessary and contingent first principles and common sense notions of the truth of the external world and the importance of ordinary facts have profound theological implications. Reid’s Christian commitments are well-worth noting. Throughout his writings, Reid makes consistent appeal to God as the author of human nature, and without whom, the external world and human nature would not exist. Ontologically, we must assume God’s existence as the basis for all things. Epistemologically we must start with ourselves, assume the certainty of the external world, and operate with the awareness that we are creatures with agentic powers. Reid is right, I think, when he argues that this is how ordinary people actually live their daily lives.

There is in Reid’s common sense epistemology, the basis for an effective transcendental argument. When non-Christians argue against the Christian truth claim, they must invoke Reid’s common sense first principles (or categories much like them) to argue against Christianity. How is such a thing even possible on non-Christian presuppositions–especially those of materialism? How does logic work in a chance universe with no creator or designer?

Several additional points are worth making. Plantinga frames Reid’s first principles in terms of belief in God as “properly basic.” If we can believe that other minds exist without any reasons whatsoever–a belief we cannot prove–on what basis then is belief in God declared irrational? Plantinga uses this “unprovable starting point” to argue against “foundationalism” (i.e., the notion that we must have sufficient evidence which “proves” the validity of our starting point). But is not Reid’s "soft" foundationalism much better? When we seek to get behind our common sense first principles, we immediately encounter the God who made us capable of using them.

I am also of the opinion that Reid’s doctrine of first principles helps clear up the primary weakness permeating Van Til’s version of presuppositionalism. Van Til’s apologetic is built upon the conflation of the order of knowing (epistemology) and the order of being (ontology). I agree fully with Van Til, when he insists we could know nothing properly if there were not a God who created all things and made us as his image-bearers. Van Til, however, insists that a truly Christian epistemology begins with the ectypal knowledge of God given in and through God’s self-revelation (Scripture).

But this raises two seemingly insurmountable problems. The first is that it is psychologically impossible to begin the knowing process outside of ourselves, apart from any prior self-consciousness. Only God can start the knowing process with himself in this sense. As his creature, and despite Van Tilian protests to the contrary, I simply cannot start where Van Tilians insist that I must (with the revelation of God). As a creature who receives this revelation externally, I can only begin with self-awareness, knowledge of the world around me, and of my own agentic powers. Unless the knowledge of God which Van Til insists upon is innate and hard-wired within me, and is available and clear to me from the first moments of my self-consciousness, I need all such external revelation confirmed as revelation coming from God. Descartes’ ugly question resurfaces at this point. “How do I know this revelation is from God and not from the devil?” My own doubts will emerge as well. “How do I know this knowledge is from God and not the product of my own vain imagination?” Completing religious claims also surface. “Why the Bible and not the Book of Mormon or the Koran?”

At this point, it is helpful to distinguish general from special revelation. Paul speaks of God’s revelation in nature as plain to all (Romans 1:19-20) as well as God’s law as written upon the human heart (Romans 2:14-15). This is general revelation. Furthermore, we bear the divine image and retain the sense of divinity. But does such knowledge of God given through the natural order include knowledge of the Trinity, the person of Jesus and his redemptive work on my behalf? No. The nature of God and his saving work in Christ is revealed to me externally in God’s word, which is the record of his redemptive words and deeds (special revelation). As B. B. Warfield once put it when addressing this very issue, “it is easy, of course, to say that a Christian man must take his stand point not above the Scriptures, but in the Scriptures. He very certainly must. But surely he must first have the Scriptures, authenticated to him as such, before he can take his standpoint in them” (Warfield, “Introductory Note,” to Francis Beattie’s Apologetics, 98-99; note: this same statement appears almost word for word in Warfield’s “Review” of Bavinck’s De Zekerheid des Geloofs,” 115).

As Van Til made plain his allegiance in this regard, declaring “I have chosen the position of Abraham Kuyper” (Van Til, The Defense of the Faith, 264-265), so too, I must declare that I have chosen the position of B. B. Warfield.

Reid does not ask us to begin with a theory of ideas or a priori categories (as with Kant), or even by presupposing the entire system of Christian doctrine (Kuyper, Bavinck, and Van Til). Instead, Reid asks us to start with an epistemological method, or better, with a particular kind of awareness of the external world and how it works common to all. When John Frame raises the presuppositionalist challenge that “`starting with the self’ leaves open the question of what criterion of truth the self should acknowledge, so `starting with reason’ leaves open the question of what criterion of truth human reason ought to recognize” (Frame, “Van Til and the Ligonier Apologetic,” in The Westminster Theological Journal, Volume XLVII, Fall 1985, number 2, 285-287), Reid would likely answer, we utilize “those criteria [first principles] we are born with, given us by our Creator.” These criteria are not a matter of a choice of a priori interpretive categories, but rather an appeal to recognize those rational faculties with which we are born, and which we spontaneously utilize.

Embracing Reid’s common sense first principles allows us to begin the knowing process with human consciousness, while at the same time asserting that such would not be possible apart from a creator. This is, I think, a healthy corrective to Van Til’s presuppositionalism.

Second, although there are several areas in Reid’s thought which orthodox Reformed Christians might find problematic–especially Reid’s endorsement of natural theology, along with the telling absence of any discussion of the effects of Adam's fall upon human nature–we do not need to follow Reid in every area of his thought to appreciate and draw upon his insights regarding first principles and the related common sense tests for truth. As Paul Helm points out, there is nothing intrinsic to Reid’s common sense philosophy which is antithetical to Reformed doctrine (Helm, “Thomas Reid, Common Sense and Calvinism,” in Hart, Van Der Hoeven, and Wolterstorff, eds. Rationality in the Calvinian Tradition, 86-88). Whatever theological weaknesses may exist in Reid’s overall philosophy can be mitigated by considering how the Old Princetonians (especially Warfield) were able to utilize SCSR as modified in light of the Reformed doctrine of the noetic effects of sin, and the necessity of regeneration as prior to faith.

Warfield was, to my mind, on the right track when he argued that the certitude of the truth of Christianity “is at bottom nothing other than the conviction that God is in Christ reconciling the world with himself . . . . It is only by the direct act of faith laying hold of Jesus as redeemer that we may attain either conviction of the truth of the Christian religion or the assurance of salvation.” Such a faith is not a blind or ungrounded epistemological leap into the dark. “For ourselves,” Warfield writes, “we confess we can conceive of no act of faith in any kind which is not grounded in evidence: faith is a specific form or persuasion or conviction, and all persuasion or conviction is grounded in evidence” (Warfield’s “Review” of Bavinck’s De Zekerheid des Geloofs,” 112-113).

We can hear the loud echo from Thomas Reid in Warfield’s conception that faith requires sufficient grounds in evidence. But this echo also requires additional biblical qualification. The reason why people do not believe the gospel is not that there are insufficient reasons given by God to provide grounds for faith. God gives evidences which meet the needs of our “common sense” tests for truth–Jesus was raised from the dead, or he wasn’t. This claim is intelligible to Christian and non-Christian alike.

The reason why people reject a gospel with sufficient grounds to believe it is because of human sin–a point not directly addressed by Reid. The biblical record is crystal clear that all the members of Adam’s race inevitably suppress God’s truth in unrighteousness (to use Paul’s language). Like Reid, Warfield believed that all humans possess the innate capacity to believe the gospel because the evidence demonstrates that Christianity is objectively true. But Warfield also understood full-well the damage wrought upon us by the Fall. Warfield speaks to this directly when he describes the pre-fall consciousness of humanity as reflecting a “glad and loving trust” in the Creator. After Adam’s fall, human consciousness was distorted to the point that it now reflects a profound sense of distrust, unbelief, fear, and despair in relation to the Creator. As a consequence, we sinful humans no longer possess the subjective ability to respond to Christian truth claims in faith (116).

The problem is not a lack of evidence for the truth of Christianity, but rather a universal and sinful unwillingness to believe that the facts of God’s revelation which are in themselves worthy of our trust. It is the Holy Spirit’s supernatural work to give the sinful human heart a new power to respond to the grounds of faith given by God (i.e., Christian evidences), which are sufficient to persuade anyone and already present in the mind (115).

The subjective certainty of faith of which Scripture repeatedly speaks therefore must be supplied by the Holy Spirit in the hearts of the elect, through the preaching of the gospel, a message grounded in the God-given evidences for the truth of Christianity. The Holy Spirit creates this subjective ability not through additional evidences for the truth of Christianity (as though the evidences God has given are insufficient), but through a supernatural act of new birth. People who are dead in sin will not believe until made alive. Yet as Warfield reminds us, “the Holy Spirit does not produce faith without grounds” (115). Those grounds include those Christian evidences associated with the preaching of the gospel.

Third, Reid’s “common sense” tests for truth fit quite nicely with the kind of truth claims the biblical writers actually make when they use arguments from contingency and causality (God made the world) as does Paul in Acts 14:15-17. Reid’s stress upon the objectivity of facts (grounded in our direct perception of the external world) seems to square with Paul’s appeal to Jesus’ resurrection as confirmation of the truth gospel he preached to the Athenians (Acts 17:31). The biblical writers never seek to prove the existence of God, although they do point out that God is the ultimate cause of all things and the Author (to use Reid’s term) of human nature. Paul is not shy about telling the Athenians gathered on Mars Hill that one of their own poets had declared, “in him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Neither Paul, nor any other biblical writer for that matter, asks his audience to “assume Christian presuppositions for the sake of argument,” so that they can understand the content of what is being proclaimed. Paul’s appeal is to a God whom his audiences already know and to a knowledge they presently possess but which is sinfully suppressed. When Paul proclaims that the resurrection (as an historical event) is the proof that his preaching about Jesus is true, Paul need not explain what he means, nor defend the possibility of miracles. It is a very “common sense” kind of claim to preach that Jesus was crucified on a Friday and raised bodily from the dead three days later. Everyone who heard Paul preach–without prior critical reflection or philosophical sophistication–grasps the significance of that claim.

Impossible as it may seem, if Jesus was raised bodily from the dead, then Paul and his gospel are vindicated. His message is to be believed and embraced. His claims can be rejected, or dismissed, only upon on self-consciously prejudicial grounds. People do not like the implications of Paul’s preaching precisely because they do understand the all-encompassing nature of Paul’s truth claim. People, then, as now, do not like to acknowledge they are guilty before God and in desperate need of a Savior. They may reject Paul’s gospel, but Jesus' tomb is still empty. The “proof” which God has given still stands over them like the proverbial “Sword of Damocles.” This fact alone establishes the truth of Paul’s claim and will convict those who reject until they die, or they manage to shove it from their consciences, or until they embrace it.

Finally, Reid’s notion that common sense is universal gives us an important way to establish non-neutral common ground with non-Christians. Instead of the “us” (regenerate) against “them” (unregenerate) a priori categories, Reid begins with universal common ground–the external world and everything which happens in it. But the non-Christian must live and operate in a world which cries out that it was created by God and we as creatures can navigate that world only because this is how God made us. There is common ground (as Paul was able to find with Jews and Greeks) but no neutrality (also seen in Paul’s direct challenge to Greek pagans). This opens wide the range of effective apologetic arguments.

Conclusion:

Although long overlooked, Thomas Reid’s philosophy of common sense offers a very useful way of establishing non-neutral common ground directly in human nature. This is important in an age of supposed self-authenticating religious truth claims such as ours. Transcendental arguments such as Reid’s are especially helpful because they force non-Christians to justify their arguments against Christianity. From where do these arguments against Christianity come, and how can they be justified? Non-Christians struggle to answer these questions. Reid gives us a helpful and practical way to exploit this weakness.

Reid’s notion of truth as objective and immediate (i.e., apart from a priori categories and ideal theories) clearly echoes the approach taken by the Apostle Paul and provides an epistemological footing for the chief argument in defense of Christianity, Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. For those who wish to integrate apologetic arguments into evangelistic contexts, Reid offers a suitable (and non-philosophical) epistemological justification for Christian truth claims. Should someone predict their own resurrection and then rise again (Jesus), the only conclusion is that proclaimed by Paul; God has given us proof, proof which is grounded in the facts of revelation (Acts 17:31). The declaration "He is risen!" requires nothing but "common sense" to fully understand. But only the Holy Spirit can enable those who understand to truly believe.

May the Reid resurgence continue!

Reading Reid:

The two volumes of Reid’s collected Works (the Hamilton edition) are available as free downloads (in PDF). Reid’s three main works, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, (1864) Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (1785), and Essays on the Active Powers of the Human Mind (1788) are included in Reid’s works, but are also widely available as separate volumes. These three volumes are offered together on Kindle for a very reasonable price

If you wish to merely sample Reid, I would recommend the paperback volume edited by Ronald Beanblossom and Keith Lehrer, Thomas Reid: Inquiry and Essays, in the Hackett Classics Series. This volume is still in print, if you want to purchase a new edition. But there are plenty of used copies readily available on-line–cheap. The introductory essay is worth the price of the book.

Highly recommended is the on-line article on Reid by Ryan Nichols and Gideon Yaffe in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reid/

Also highly recommended are the Oxford University Lectures on Reid and Hume given by Daniel N. Robinson, https://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/series/reids-critique-hume. These lectures awakened me from my dogmatic slumbers a while back. I’ve been reading Reid every since!

Books About Reid:

Cuneo and Van Woudenberg’s The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Reid, contains a number of useful essays on Reid’s work including essays on common sense, perception, and religion.

Alexander Fraser’s Thomas Reid, in the Forgotten Books Series is dated, but provides a good introduction to Reid’s life and career.

Keith Lehrer’s Thomas Reid, is highly recommended–although out of print and hard to find. This is, in my opinion, the best introduction to Reid’s thought.

Dugald Stewart’s “Life of Thomas Reid,” is found in volume one of The Works of Thomas Reid, and provides an early treatment of Reid’s life and work by his chief disciple.

Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology is an interesting book, focusing upon Reid’s utility for Reformed Epistemology.

Books About Scottish Common Sense Philosophy (SCSR)

S. A. Grave’s, The Scottish Philosophy of Common Sense remains the best single volume treatment of Scottish School. You have to go to a library to find a copy

James McCosh’s The Scottish Philosophy, is a useful history of the individual figures in the Scottish School. You can find this as a PDF download.

Daniel Sommer Robinson’s The Story of Scottish Philosophy: A Compendium of Selections from the Writings of Nine Preeminent Scottish Philosophers, with Biobibliographical Essays, is an anthology of Reid and others. Includes Reid’s correspondence with Hume.