"A Day That Will Live in Infamy" (Re-post)

Tuesday, December 7, 2010 at 10:00AM

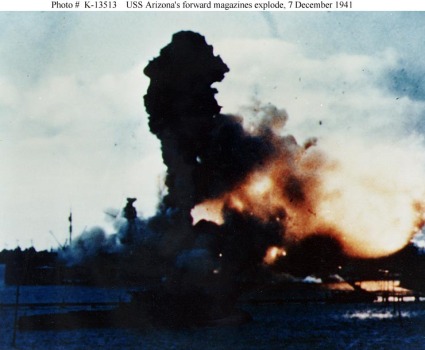

Tuesday, December 7, 2010 at 10:00AM  My parents spoke often of the shock of learning of the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It was an event which brought the United States into the war and which defined their entire generation.

My parents spoke often of the shock of learning of the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It was an event which brought the United States into the war and which defined their entire generation.

Throughout the years I have been privileged to talk with several men who were at Pearl Harbor the morning of the attack. To a man they expressed the same reaction: Initial shock, increasing anger and a desire for revenge, then relief and thankfulness for their own personal survival, followed by the grim realization that a long and bloody war had only just begun.

My father was an FBI agent during the war and spent his time monitoring various points of entry into the US (mostly cargo ports in Philadelphia, Miami, but also the US/Mexico border near El Paso). For him, the war years were tedious and routine, but he saw his work as necessary and important.

My father-in-law, a rancher from a small town in Nebraska, served in the Army Air Corps in the Pacific Theater. He lived his entire post-war life in the shadow his war experience. He saw things men should never see and had some wonderful stories to tell about his South Pacific adventures. Throughout his life he stayed in touch with the men of his bombardment group (he serviced the B-24s his group flew into combat). His war service defined him.

The greatest generation of citizen soldiers won that war against the forces of fascism and totalitarianism. They were better men than I, and sadly, their number declines by the day. But sixty-nine years ago, their world changed. And so did ours. Lets not forget them, nor their service and sacrifice.

Reader Comments (38)

What some 2kers are also trying to say is that your appeal to military and political judgement also goes across the board, so that whether or not to protest a city ordinance on private meetings or the failure of the Constitution to include an amendment on the Lordship of Christ are also matters about which political or prudential judgments are required.

Your nuance only seems to apply to your black and white reading of those who share your judgments or not.

But also interesting is the appeal to the exceptional clause, which isn’t unusual. It seems to me the burden is always on those who want to say that something is an exceptional case and the church should break with her general rule to stay silent. And it seems to me that nine times out of ten it ends up being something one simply doesn’t like or otherwise enjoys popular disdain, like the slavery and the Third Reich. (Why don’t Stalin’s or Mao’s regimes ever make the cut? Their numbers alone beat Adolf’s.) But how is it obvious that the American enslavement of Africans was an exception but internment of Asians isn’t, such that the church should pipe up in one but not the other? The point isn’t to defend the slavery, internment or the Holocaust, it’s to still wonder why the church should invoke the exceptional clause for some things when there are plenty of other violations in the world that get silence. One option is for you to get consistent and suggest the church condemn more political stuff, but that only gets you into the problem of the church becoming more distracted from her sole calling, which is to hold out the unfettered gospel.

I will repeat, that individual Christians have liberty to involve themselves in political movements and causes or not according to their prudential judgments (some have time, gifts, and interest in cultural and political matters, and others do not). There is no hard and fast rule in Scripture I know of that all Christians should or should not campaign for candidates or ballot measures or causes in any specific case. But as I have consistently said, Christians are also citizens of the city of man, the U.S., and have civic duties to be good citizens in the common realm. We are citizens of the U.S. and not only the kingdom of God. And as Dr. Van Drunen, Cranfield, as a general rule Christains should involve themselves in their individual capacity in public affairs, on a number of grounds. Oiur goal is not to "transform" or "redeem" the civil sphere, but modestly improve it and work for justice and mercy.

Dr. VanDrunen persuasively says it well:0

"However, this is not to say that we as Christians should not participate in the culture war, and it does not mean that all the methods or goals of those on the frontlines of the culture war are wrong. Not at all. God commanded the people in Jeremiah 29 to seek the peace and prosperity of the city in which they lived, and this applies to us as well. We know that a nation with increasing numbers of cocaine-addicts, abortions, thefts, child-abuse cases, illiterates, etc., etc., will not retain desirable levels of peace and prosperity for long. Therefore we do have an obligation to do things which will, if not eliminate such things, at least substantially reduce their rate of occurrence. The peace and prosperity of our society, not to mention our personal peace and prosperity, depend on it. And the political sphere certainly is one of the institutions of culture which will make its indelible stamp on the peace and prosperity of the society. Christians therefore should have an interest in the political process when their form of government allows it, as ours does. To turn our backs on politics would mean to turn our backs in part to the command of God to seek the peace and prosperity of our nation. We may debate amongst ourselves which political positions to promote and how much emphasis should be given to the political process, but the interest and involvement in politics which we see among the “religious right” is in itself a good thing. But, it must always be accompanied by the realization that we are participating in the politics of Babylon. What should we hope to gain by our cultural, including political, activity? Only a relatively better life for society, ourselves, and our children in the years to come than what we would otherwise face. We seek not the destruction of our enemies, but simply a modestly better society ...."

But I am familiar with the quote. I have no qualms with it inherently. But my question in response to its apparently positive view of so-called “culture war” is what about those of us persuaded that “culture war” actually is a bad way to engage our society or not the best way to have beneficial influence on the city? We’re agreed that culture war can often times be a confusion of the kingdoms, which is a problem for those of us who confess the doctrine of the two kingdoms, but I don’t think that is its only problem. It is also a problem for those who don’t confess anything about the two kingdoms, which is to say that it is a common or human issue. Some of us, believers and non-, see much more value in relating to our neighbors in the common realm in ways less political and more human. Culture war is a way to tear at the very social fabric warriors, believing and unbelieving, ironically say they want to mend and nurture. So, on principle, VanDrunen is exactly right, but in practice it might be that some of us have different ideas about what it means exactly to have a beneficial influence in the common realm we robustly inhabit.

You're also making false dichotomies. The choice is not "relate to neighbor in ways less political" or full on culture war. Christians should relate to their neighbor as humans rather than warriors, but it is also appropriate to engage in the political process in our individual capacity since we're citizens of the city of man too. You are grossly over-reacting to the excesses of the Christian Right and trying to impose a flat, "quietist" or pacifist position as what is "wise" for all Christians. If you want to be a quietist or pacifist, and don't want to be political, I have repeatedly said I have no problem with that. My only beef is when you reflexively criticize those who exercise their liberty to be poliitial. That's when you go after them as "unwise." We have to use judgment to determine which activities are wise, not categorically say alll are unwise, all are "culture war."

My purpose was not to make an argument, but if it were, Zrim's discussion of the exception clause would be my point. Why is it wrong? Because the Japanese-Americans were CITIZENS. They were not aliens living in our country. These people were US Citizens who did absolutely nothing wrong. The Constitution is supposed to protect all of our Citizens from just this sort of thing. Any use of an exception clause is fraught with peril. That is the point; that is the argument.

BTW, I can't wait to see who made the quote just posted.

This is somewhat of a redirect from your interactions with Zrim and DGH here, simply because I don't have the time to engage that discussion. However, I have some disagreement with the moral merits of US policy in WW2, especially regarding our willingness to bomb heavily populated areas where there would be a great many civilian casualties. I do think you are right when you assert that we have to take these (military) policies in their own context, and evaluate the merits of these policies on the basis of the information that was available at the time the policies were initiated. I'll preface my comment by saying that the bravery and sacrifice of American soldiers, marines, pilots [and even the Navy I guess :)] was indicative of what is great about our country, and even if there are areas that I offer criticism of WW2 military policy I do believe it was a just and necessary war. However, in the last 5 years or so, I have become more critical of the policies, especially the ones that surrounded US air-strikes in heavily populated areas (e.g. the fire-bombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities, as well as Hiroshima/Nagasaki). One of the more influential criticisms that changed my mind from a carte blanche support for these airstrikes was the lengthy interview of Robert McNamara in <i>The Fog of War</i>.

As McNamara reflected on the bombing of Japan under the leadership of Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, he explains the thought process and justification of the bombing of Japan between Oct. 1944 and Aug. 1945 that killed upwards of 500k civilians and expresses his regrets and criticisms surrounding these policies 60 years later. He rightly contextualizes these policies in their time, and I believe reasonably makes the case that it is unlikely that Americans, or the rest of the Allies or the Axis would have adopted any other bombing strategy. Suffice to say, the man who was responsible for the death of likely over a million people from WW2 through Vietnam, all under the rubric of ostensibly just wars insisted that we must do better to mitigate the death of innocents in war. He draws many other interesting conclusions, and I would recommend the film to anyone.

All of this to say, while I am not sure how we could have fought WW2 differently than we did it is hard to make a moral justification for the merciless bombing of our enemies, Japan in particular. We essentially bombed these nations into submission, and maybe it preserved American lives, however it was at the expense of at least 500k non-combatants. I would be more inclined to say that these bombings are as a result of the tragedy of war rather than looking for a moral high ground. To our nation's credit, since Vietnam we have done a far better job on minimizing the deaths of innocents, it is just unfortunate that we didn't contemplate that earlier in our history

Yes, I am critical of what Hunter describes as the "turn to politics," but then again you want to say he's no expert in some technical sense so his work is to be summarily dismissed. Huh?

Merlin, you may not be following me. I'm not making a constitutional point, I'm making a spirituality of the church point. It may well have been politically wrong (actaully, I'm inclined to think it was), but what of what spiritual interest is that to the church? Are you saying that the internment was an exceptional instance in WCF 31.4, such that the church should issue an explicit condemnation of it?

You're correct that U.S. military doctrine today is much more careful about collateral damage and much more opposed to misconduct by our military. I was in the service and learned about the differences between our military's approach today v. WWII. That said, I think on balance the record of the U.S. in defending freedom and protecting American and Allied interests is unparalleled in the annals of history.

I get where you are coming from here. The justification was based on the research at the time. However, by the time the US took Okinawa, Japan had zero chance of winning the war (truth be told it was likely much earlier than that). So the threat of a West Coast invasion may have been used to rally support on the home front, but the Japanese didn't have the means to launch the invasion after the US crushed their Pacific fleet. All I am arguing is that from the vantage point of history, we can say that there may have been better options to end the war other than bombing Japan and her people into surrender. Admittedly the bushido culture that pervaded Japanese culture and gov't at the time would have made it difficult to coerce a surrender by any means, but we didn't just go after Japanese military, we went after Japanese people and that's where the moral waters get muddied. Sadly, I think there were other factors at play that made the bombings more expedient - America was loosing it's stomach for the war at that point; war bonds weren't selling like they were before the fall of Nazi Germany, and the US didn't want to embroil themselves in an unpopular quagmire. Right or wrong America doesn't have much of an attention span, culturally, we are ill prepared for the sacrifices necessary to win a lengthy war. I think that this had as much to do with our decision to bomb as an aversion to invasion. If moral analysis was centered upon preserving civilian life, we might have been more inclined to slug through a costly invasion. But this is hindsight, and if I were involved, I likely wouldn't have chosen differently.

My guess is if such action was universally justifiable, then you would think that we would employ the same sort of tactics, but the fact that Iraq and Afghanistan aren't parking lots today says a lot about what we have learned. Anyhow, I'd recommend the movie, it is really thought provoking even if you disagree. I have some other business to tend to so I'll give you the last take on the issue.

Thanks. I'll make a point to watch the movie. I"m don't place much weight on anything McNamara says. All these facts are highly disputed by military analysts and historians. The best contemporary analyses I've read still estimate that an invasion of Japan could have cost a million U.S. military lives, and untold numbers of Japanese lives.

I've read a good deal of contempary revisionist history that faults the U.S. My sense is that most of the authors have an ax to grind and some pretty palpable anti-American animus.

1) The US dropped not 1 but 2 bombs on civilian population centers. Perhaps one might debate Hiroshima, but what justifies Nagasaki? Wasn't the point of superior destructive capacity already made?

2) And again, the idea of the civilian population center. Sure Japan was persistent, but it's like saying "we're going to slaughter hundreds of thousands of your civilians including women, school children and infants to get you to back down." Not to mention the many who survived to die slow deaths from radiation poisoning. Now I don't know what your take on 9-11 was, but if the terrorists are to be called cowards for targeting American civilian centers instead of facing off with the military machine, are we consistent to attempt to justify the way the A-bombs were used? Was a civilian center really necessary to demonstrate its destructive might?

And by the way, I am neither anti-war nor "anti-American."

It is apparent that you have not read the literature of the period. Your comments betray a lack of familiarity with the facts. The burden is on you to explain why your military judgments, unencumbered by the facts, are superior to the judgments of top military and civilian defense experts of the day, who considered dropping two bombs an act of military necessity.

I gave you my take (which, in my ignorance, seem to be a VERY compelling case against dropping said bombs) and I'm asking you to help me reconsider those prejudices. If you condescend to share some of those insights with me rather than sit pretty on your superior knowledge, perhaps I could learn something? I've only asked for 5-10 of your top reasons... hopefully ones that could directly address my concerns? Thank you.

I am not sure how well-read you expect someone to be on a subject, to lack the willingness to give even a few pointers of where you believe I might find a profitable primer on the issue. I'm sure you're aware that web searches often involve having to cut through a ton of dross.

I'm also not sure why you are unable to provide a couple of short thoughts I might pursue and chew on (e.g. what makes so many civilian deaths acceptable collateral damage... or were they collateral or part of the intended target?). I may not be terribly read up on this incident of history (I've focussed much more on antiquity and the middle ages), but this does not make me entirely incompetent at weighing issues if given more data. I do have 3 graduate degrees, so I don't think I'm entirely stupid and unworthy of education. And being Chinese, I probably have more reason to be bigoted against the Japanese than against the Americans, considering what they did to us (I did read "The Rape of Nanking" ... that might count as at least one WW2 book I've read).

So may I ask again if you might be gracious enough to help out someone here who is casually but genuinely interested in the question?