"Children in the Hands of the Arminians" (Part Two)

Wednesday, March 21, 2018 at 11:57AM

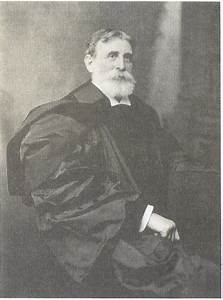

Wednesday, March 21, 2018 at 11:57AM  Here is part two of B. B. Warfield's "Review" of The Child as God's Child, by Rev. Charles W. Rishell, Ph. D., Professor of Historical Theology in Boston University School of Theology. New York: Eaton & Mains. Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham (1904).

Here is part two of B. B. Warfield's "Review" of The Child as God's Child, by Rev. Charles W. Rishell, Ph. D., Professor of Historical Theology in Boston University School of Theology. New York: Eaton & Mains. Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham (1904).

Warfield's review of Rishell's book was originally published in vol. xvii of the Union Seminary Magazine, 1904. Warfield entitled his review, "Children in the Hands of the Arminians."

To read the first in the series go here: Children in the Hands of the Arminians -- Part One

We pick up where we left off last time . . .

________________________________

Warfield contrasts the logical consequences of the Arminian "indifference to the religion of childhood," with those whom Warfield identifies as "sacerdotalists"--i.e. the Roman Catholic notion that the saving grace of God is mediated through the sacraments of the Roman Church--(see B. B. Warfield. Plan of Salvation, 52-69).

This much, at least, must be allowed: that in no other than Arminian circles could such indifference to the religion of childhood, or to the recognition by the church of the membership of Children in it, as is here charged, intrench itself in the recognized principles of the system. The sacerdotalist holds that in baptism God has placed in his hands the instrument by which the child of the tenderest years may be incorporated into the church and into Christ. Failure to baptize any child to whom he could obtain proper access would be to him a crime against humanity and against the love of God. Failure to recognize all baptized children as members of the mystical body of Christ would be to him blasphemy against the holy ordinance and the power of the Spirit of God which works through it.

If the Arminian's theology logically leads to an "indifference" in the spiritual development of children (who must reach an age when they can personally appropriate the grace of God), the sacerdotalist goes to the opposite extreme. Since God's sacramental grace actually and truly incorporates every baptized child into Christ and his church, then the very thought of delaying baptism until the child can grow to sufficient maturity to "choose" Christ and be baptized as an act of obedience, is tantamount to denying that God's grace is applicable to children.

The Reformed view--grounded in the covenant of grace--categorically rejects both the Arminian and sacerdotalist view of children.

The Reformed Christian, suspending salvation for all alike upon the sovereign grace of God alone, operating in accordance with God's covenanted purposes of mercy, points with confidence to the terms of the promise, "To you and to your children." He enjoins parents who trust in the covenanted mercy of God, therefore, to present their children, on the credit of this promise, to the Lord in baptism, and to bring them up in His nurture and admonition. And he enjoins the Church to recognize them by means of this holy ordinance as God's children, heirs of all the promises; and to take order for their training as such, that they may adorn in life and conduct the Gospel by which they are saved. Failure to recognize them as the children of God would be to him treason against that very covenant in whose terms he finds all his own warrant for hope and peace.

The Reformed view sees children of believers as members of the covenant to whom the sign and seal of the covenant (baptism) ought be applied. The condition is the parent's "trust" in God's promise--i.e., "the covenanted purposes of mercy," knowing that God's grace in election, not the act of baptism, is the ultimate ground of salvation. Nevertheless, that Christian parent who presents their children for baptism are to view them as members of Christ's church (which they now are), and who thereby assume the joyful responsibility of raising these children in the nurture and admonition of the Lord.

But, says Warfield,

The Arminian, on the other hand, strenuously contends that all that God has done, or does, looking to the salvation of man has been done with reference to the mass; and that the salvation of the individual absolutely depends, therefore, on his own improvement of the universal provision. He is under constant temptation, therefore, to look upon the individual as outside the Church - the company of God's people - until by his own act of choice of Christ as his portion he has incorporated himself into it. This means, of course, an inherent tendency in the logic of the system "to count the children out."

On the Arminian scheme, as we have seen, children must be "counted" outside the church until they can include themselves. The Arminian logic dictates that children remain outside the covenant, and therefore outside the church. Such a view, no doubt, explains the wide-spread sentiment among today's evangelicals that Lord's Day worship is for adults only, that children should be excluded from the ordinary Lord's Day service. Children are not to be welcomed into worship (though "children's church" is often provided), until capable of "adding themselves" to the people of God.

Warfield points out the fundamental problem with the Arminian view.

If the incorporation of the individual into Christ and therefore into His Church depends on his own voluntary act of intelligent choice, how, indeed, can children as yet incapable of choice be "counted in"? One would think it tolerably clear that they would be "counted out" until they arrive at such years that they may intelligently and voluntarily "count themselves in."

Given the Reformed understanding of children as baptized but not yet professing members of Christ's church, Warfield is pleased with Dr. Rishell's efforts to include children in the church. But Dr. Rishell must live with an obvious theological inconsistency to do so:

Dr. Rishell's effort to correct this sad state of things among our Arminian brethren must, of course, meet with the deepest sympathy of every Christian heart. Only we cannot say that he goes about his task in a very hopeful way. Obviously, the root of the difficulty lies in the Arminian doctrine of the function of the human will in salvation. But Dr. Rishell does not attack the problem by seeking to correct this error. From all that appears he is himself firmly holden in it, and would think of nothing so little as commending to his brethren a frank abandonment of their fundamental postulate of autosoteric [Greek: self-saving] Christianity.

Warfield points out and then addresses Rishell's proposed solution to the problem deeply inherent within in his Arminian theology.

[Dr. Rishell] elects to approach the problem, therefore, from another angle, and seeks to meet the difficulty by bringing into prominence another doctrine of at least Evangelical Arminianism. This is a doctrine which, as Dr. Rishell suggests, has fallen somewhat into the background in the mind of the average Arminian - as well, indeed, it might, seeing that it clearly stands in direct contradiction to the fundamental Arminian postulate that in the salvation of the individual everything depends upon his exercise of his own power of free choice. This doctrine is that postulate by which the Wesleyans have sought to cure the pelagianizing tendencies of original Arminianism by declaring, to put it somewhat roughly, that all men come into the world already saved. That at least is the way the old Evangelical Arminianism put it, though no doubt a new Arminianism - which is much the same as the old Rationalism - may prefer to phrase it that all men come into the world "safe."

Since universal grace is potentially available to all (providing a sort of "safe zone"), one must willfully reject Christ to remove oneself from that sphere where grace operates. To put it crudely, "you have it in you to take advantage of what is possible--the possession of the merits of Christ through faith--if only you do not reject it."

The idea of a universal prevenient grace becomes Rishell's basis then for seeing children as coming into the world as already "saved" and to be treated as such. What they need, in Rishell's estimation, is training by the church to ensure they stay saved. The goal of the church is to foster their "innocence" by helping to preserve that which they already have--the universal, if merely potential, grace of God.

This doctrine, it seems, has, in its more evangelical form, stood in the thought of Arminianism heretofore rather as a theoretical postulate saving its theoretical evangelicalism, than as a practical principle of thought and action. Dr. Rishell proposes to bring it out of its position of "innocuous desuetude." and to make it the basis of recognizing children as the children of God, demanding recognition and treatment appropriate to that condition. The fundamental proposition of Dr. Rishell's book becomes thus the hitherto, as it seems, somewhat neglected Arminian doctrine that all children are born into the world in a state of salvation. His contention is that, this being the case, children are not to be looked upon as subjects who are to be saved. They must not be dealt with therefore as subjects who are to be trained for salvation. They are rather to be thought of as already saved; and are to be treated as needing to be trained only to preserve intact the salvation of which they are already possessors.

This, you have no doubt noticed, is nothing but older phraseology for the now common evangelical doctrine of an "age of accountability," wherein children are to be considered "innocent" before God until they are capable of subtracting themselves.

Warfield calls attention to the price Dr. Rishell must pay to think of children like this; to reject the universal guilt of original sin, as well as the inherent corruption which passed upon our entire race via the Fall of Adam.

He spares no emphasis or reiteration to make this fundamental proposition plain. And he omits no effort to give it validity - in his entire conception of the work of the parent and child in child-training. Children, having no guilt of original sin, need no forgiveness. Being already in a state of grace, they need no conversion. They are at least as free from corruption and as well-placed in every respect as adult converts (see e.g., pp.34, 37, 38, 41, 43, etc.). They ought not to be taught, therefore, that they require a Savior. They ought not to be told that they are to repent of their sins, and to rest on the Savior in faith, and faith only. They ought rather to be instructed that they are in a state of grace, and that they need only to preserve intact that good thing that has been committed to them.

Instead of seeing themselves as sinners in need of a Savior, or seeing themselves as needing to "add themselves" to the people of God (on consistent Wesleyan-Arminian terms), rather children need to be told they have already been added to Christ, and it merely remains for them to stay "added."

This, of course, depends upon the notion that grace is universal but merely potential (not effectual), and thereby subject to human determination. We can choose to either add ourselves, or subtract ourselves from Christ through sin and apostasy. Rishell's solution--"don't tell children to add themselves, tell them they have already been added." The catechesis of the church which believes this becomes "teaching them not to subtract themselves," which almost always leads to an emphasis upon moral conduct--"be nice Christian children."

End of Part Two --More to Follow

Reader Comments