Who Was Thomas Reid and Why Does His "Common Sense Philosophy" Still Matter (Part One)

Tuesday, July 31, 2018 at 02:56PM

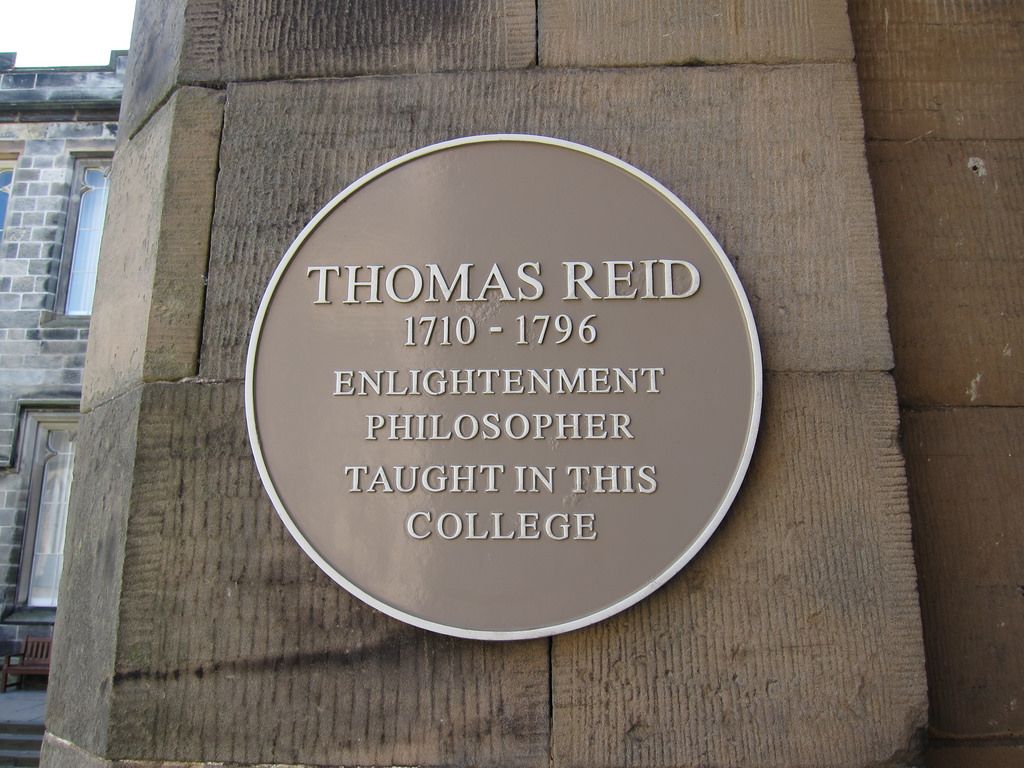

Tuesday, July 31, 2018 at 02:56PM  Reid's Official PortraitThomas Reid (April 10, 1710 – October 7, 1796) is best known as the founder and principal philosopher of “common sense,” or more properly, “Scottish Common Sense Realism” (SCSR). Reid was highly respected and quite influential in the days of the eighteenth century Scottish Enlightenment, but the popularity of Reid and his common sense philosophy quickly faded in subsequent generations. Although destined for relative obscurity, Reid’s influence did remain strong in several quarters. Of late, there has been a Reidian resurgence of sorts, reflected in several volumes about Reid’s philosophy, the publication of a new critical edition of his works (by the University of Edinburgh), and through favorable treatment by so-called “Reformed Epistemologists,” Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff.

Reid's Official PortraitThomas Reid (April 10, 1710 – October 7, 1796) is best known as the founder and principal philosopher of “common sense,” or more properly, “Scottish Common Sense Realism” (SCSR). Reid was highly respected and quite influential in the days of the eighteenth century Scottish Enlightenment, but the popularity of Reid and his common sense philosophy quickly faded in subsequent generations. Although destined for relative obscurity, Reid’s influence did remain strong in several quarters. Of late, there has been a Reidian resurgence of sorts, reflected in several volumes about Reid’s philosophy, the publication of a new critical edition of his works (by the University of Edinburgh), and through favorable treatment by so-called “Reformed Epistemologists,” Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff.

The purpose of this series is to introduce Thomas Reid’s philosophy of “common sense,” which, I believe, has been far too long misunderstood and therefore neglected, and which still has an important role to play in formulating a “common sense” apologetic for the Christian religion–an apologetic which centers in the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ as Christianity’s chief truth claim.

The Life and Times of Thomas Reid

Reid was born and raised in Strachan, near Aberdeen, Scotland. The son of a Church of Scotland minister (the Rev. Lewis Reid, 1676-1762), Reid’s mother was Margaret Gregory, one of twenty-nine children, and from the famed Gregory clan. Her first cousin, James Gregory (1638–1675), was a respected mathematician and astronomer who invented the reflecting telescope. Reid began attending Marischal College in Aberdeen in 1723, and graduated Master in 1726. Reid was only 16, but this was typical for the time. Reid was greatly influenced by his teacher, George Turnbull. Turnbull was a follower of idealist philosopher Bishop George Berkeley–Reid later came to oppose the Bishop with great vigor, as he did the empiricist philosophers John Locke and David Hume. During his time at Marischal, Reid became thoroughly acquainted with Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathmatica, and showed much appreciation for Newton throughout the course of his career.

Before becoming a philosopher, Reid served as a parish minister. He was licensed to preach by the Church of Scotland in 1731, and briefly pursued theological studies after licensure. In 1737, Reid was ordained and took a pastoral call to a small church in New Machar (near Aberdeen). While in New Machar (1740) Reid married his wife, Elizabeth. Together they had nine children–eight of whom, sadly, Reid outlived. Little is known about Reid’s ministry in New Machar, but the story circulates that he was not near as popular in the parish as was his wife. This was due to rumors that Reid was given his call through patronage–an unpopular practice in small, rural parishes like New Machar.

It is likely that Reid belonged to the “moderate party” of Hugh Blair (a popular Scottish minister). The so-called “Moderates” focused on Christian morality, not the Calvinistic doctrines found in the Westminster Standards, to which all ministers of the Church of Scotland were required give to affirmation. Reid’s sermons are lost to us, but his deep personal faith and piety is expressed in a prayer in which he praised God for his providential mercy after Elizabeth had been spared during a serious illness.

While in New Machar, Reid continued to read and study philosophy, specifically the work of Glasgow moral philosopher Francis Hutcheson and his influential book, Inquiry into the Origins of the Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. Reid also read and digested fellow Scot David Hume’s Treatise on Human Nature (1738-40). Reid’s first publication, an essay On Quantity, was published for the Royal Society in October of 1748. This is a good indication that philosophical interests–not theological matters–were driving Reid’s intellectual life even while serving in the parish.

In 1751, Reid took a professorship at King’s College Aberdeen, becoming a teacher, lecturer and regent. In accepting this call, Reid was required to give up his ordination and did so in 1752. Along with John Gregory and other notable intellectuals, Reid founded the Aberdeen Philosophical Society (popularly known as the “Wise Club”), which continued meeting until 1773. During this time, Reid completed his doctoral work, but did not publish his first book until 1764, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, when Reid had reached the age of 54. As was the case with Immanuel Kant, who claimed to be awakened from his “dogmatic slumbers” after reading a German translation of David Hume’s Treatise, Reid too was stirred by Hume–in Reid’s case by Hume’s An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, first published in 1748. Hume’s published works were a continual source of discussion within the Wise Club, and Reid’s Inquiry is thought to be largely based upon lectures developed for Wise Club discussions.

In 1751, Reid took a professorship at King’s College Aberdeen, becoming a teacher, lecturer and regent. In accepting this call, Reid was required to give up his ordination and did so in 1752. Along with John Gregory and other notable intellectuals, Reid founded the Aberdeen Philosophical Society (popularly known as the “Wise Club”), which continued meeting until 1773. During this time, Reid completed his doctoral work, but did not publish his first book until 1764, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, when Reid had reached the age of 54. As was the case with Immanuel Kant, who claimed to be awakened from his “dogmatic slumbers” after reading a German translation of David Hume’s Treatise, Reid too was stirred by Hume–in Reid’s case by Hume’s An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, first published in 1748. Hume’s published works were a continual source of discussion within the Wise Club, and Reid’s Inquiry is thought to be largely based upon lectures developed for Wise Club discussions.

David HumeReid’s Inquiry was primarily a response to Hume, but Reid also took aim at other advocates of the so-called “ideal theory.” According to Reid, in addition to Hume, those who held the “ideal theory” included Rene Decartes, John Locke, and George Berkeley. Ideal theorists placed the mind and our ideas between sensation of the external world and our knowledge of it. Ideal theorists were necessarily skeptical of the even the possibility of direct knowledge of the external world–although they never expressed their skepticism as boldly as the logic of their theories dictated. Reid, who quickly became Hume’s most powerful critic, sought to challenge what Reid identified as the “monster of skepticism” given life by Hume. If anything characterizes Reid’s philosophical work, it is his fierce opposition to all forms of epistemological skepticism typified by his Inquiry. Reid’s challenge to the ideal theorist still stands. Can your philosophy actually assure us of the existence of the external world? Or does the author (however unintentionally) ultimately drive us to skepticism by placing a representational or mental “theory of ideas” between the world which exists and our perception of it.

David HumeReid’s Inquiry was primarily a response to Hume, but Reid also took aim at other advocates of the so-called “ideal theory.” According to Reid, in addition to Hume, those who held the “ideal theory” included Rene Decartes, John Locke, and George Berkeley. Ideal theorists placed the mind and our ideas between sensation of the external world and our knowledge of it. Ideal theorists were necessarily skeptical of the even the possibility of direct knowledge of the external world–although they never expressed their skepticism as boldly as the logic of their theories dictated. Reid, who quickly became Hume’s most powerful critic, sought to challenge what Reid identified as the “monster of skepticism” given life by Hume. If anything characterizes Reid’s philosophical work, it is his fierce opposition to all forms of epistemological skepticism typified by his Inquiry. Reid’s challenge to the ideal theorist still stands. Can your philosophy actually assure us of the existence of the external world? Or does the author (however unintentionally) ultimately drive us to skepticism by placing a representational or mental “theory of ideas” between the world which exists and our perception of it.

Shortly before Reid’s Inquiry was published, he was offered the prestigious Professorship of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where he became the immediate successor to Adam Smith (1723-1790), the author of the influential Wealth of Nations (1776). Reid accepted this call and remained at Glasgow until his retirement in 1781. Productive in his retirement, Reid turned his university lectures into the books, Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (1785) and Essays on the Active Powers of the Human Mind (1788).

In these volumes on intellectual and active (and agentic) powers, Reid defends a libertarian notion of human freedom–i.e., that human agency is responsible for free actions of men and women, who are morally accountable for their choices. But Reid thought his view perfectly compatible with the Westminster Standards which prescribes the agency, but not the causality of human action in light of the mystery of “the predestination and foreknowledge of God in conjunction with the liberty of man” (Reid, "Prescience and Liberty," in Works of, II.977).

Reid also directly attacked Hume’s notion of personal identity, in which Hume famously held that human identity is nothing but the on-going memory of our experiences over time. Hume once wondered whether he still existed while he slept, and if his existence was reconstituted each morning upon awakening. Reid appreciated Hume’s wit, but held that any sequence of memories we may have is grossly insufficient to ground personal identity and self-awareness, which are common sense beliefs held by all–even by those like Hume, though the latter candidly admitted to doubting them.

One of Reid’s most effective methods of criticism of his opponents was to argue that philosophers like Hume often raised provocative questions in the safety of their private studies, boldly going against widely accepted “common sense” human convictions of the day (i.e., causality and on-going personal identity). As Reid pointed out, such men cannot live out their philosophical convictions in the real world they actually inhabit. Reid playfully jabbed Hume, stating that if he (Reid) chooses not to believe my senses, “I break my nose against a post that comes in my way, I step into a dirty kennel; and after twenty such wise and rational actions I am taken up and clapped into a madhouse” (Reid, Inquiry, in Works of, 1:184). Hume may question whether there is a third thing (causality) between the billiard ball and cue which strikes it, but presumably such skepticism never stopped Hume from playing billiards. Hume’s theory does not stop us (nor Hume) from trusting our senses.

By all accounts, Reid was a modest and humble man, well-liked, and widely respected. His obituary (in the Glasgow Courier) describes his as “a life distinguished by an ardent love of truth, an assiduous pursuit of it in various sciences, by the most amiable simplicity in manners, gentleness of temper, strength of affection, candour, and liberality of expression.”

Thomas Reid on "First Principles"

Reader Comments