"A Vice Very Common With Books of This Class" -- B. B. Warfield's "Review" of Andrew Murray's "The Spirit of Christ"

Friday, May 11, 2018 at 02:21PM

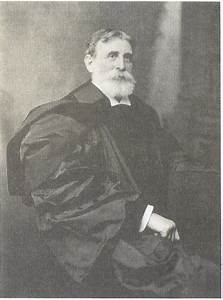

Friday, May 11, 2018 at 02:21PM  B. B. Warfield (1851-1921) is widely hailed as one of America's greatest theologians. His books have remained in near-continuous publication since his death in February, 1921. Although dead for nearly 100 years, Warfield remains a theological force with which to be reckoned.

B. B. Warfield (1851-1921) is widely hailed as one of America's greatest theologians. His books have remained in near-continuous publication since his death in February, 1921. Although dead for nearly 100 years, Warfield remains a theological force with which to be reckoned.

As professor of polemical and didactic theology at Princeton Theological Seminary, Warfield published 781 book reviews over his long and exceedingly productive career.

Some of Warfield's reviews are published in his collected works, while many are not. I thought it might be of interest to bring some of these currently unpublished "Reviews" to light.

The first review discussed in this series was Children in the Hands of the Arminians. The second was Warfield's review of C. F. W. Walther's book, Gesetz und Evangelium (Law and Gospel): C. F. W. Walther on Law and Gospel.

For the next installment in this series, I have chosen Warfield's "Review" of Rev. Andrew Murray's book, "The Spirit of Christ," published in 1888, which Warfield reviewed the following year. This book still remains in print (The Spirit of Christ) and is available from Whitaker House, a charismatic/Pentecostal publisher.

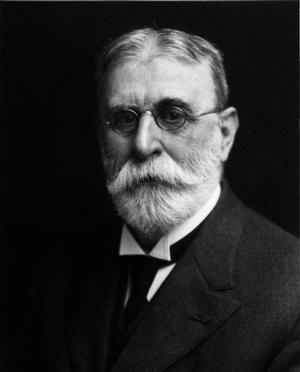

A brief word about Andrew Murray is in order. Rev. Murray (1828-1917) was a Dutch Reformed minister who labored in South Africa. Murray had a life-long passion for missions and was a champion of the South African Revival of 1860. Murray was devoted to the so-called "Keswick" theology which stressed the "inner" or "higher life." He also endorsed faith healing and believed in the continuation of the apostolic gifts. He was a significant forerunner of the Pentecostal movement--a remarkable accomplishment for any Dutch Reformed minister (I am being facetious, of course).

Murray was a prolific author, publishing more than fifty books and hundreds of pamphlets. We sold cases of them in our bookstore (when I was growing up) and for which I have long since repented. So when I first ran across BBW's "Review" of Murray's book, I was very interested in what Warfield would have to say. Needless to say, the Lion of Princeton was not terribly impressed.

_______________________________________________

Warfield appreciates Murray's warn piety and obvious sincerity, but then raises one of his longstanding concerns--reducing biblical Christianity to mystical experience.

The Spirit of Christ: thoughts on the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the believer and in the Church. By Rev. Andrew Murray. (London: James Nisbet & Co., 1888.) 394 pages. The author treats this greatest of all Christian subjects with adequate reverence and tender devoutness, but scarcely with sufficient judiciousness. The mystical spirit has been always of the greatest value to the Church, and sometimes the sole preservative of true Christianity in a materialistic or legalistic age. But no tendency requires a stricter watchfulness to preserve it from extravagance.

To paraphrase Warfield, Murray is obviously sincere, but has paid too little attention to biblical teaching. Murray's heart-felt religion is expressed in terms of personal experience, not in biblical language or expression. Warfield regarded mysticism and rationalism as polar opposites. Elsewhere he had written if you cool down a mystic, you get a rationalist. Conversely, if you heat up heat up a rationalist, you get mystic. In either case, if you ground the Christian faith in either reason or experience, and not in Scripture, you will make a mess of things--as Rev. Murray has done.

Mr. Murray’s mystical tendency shows itself especially in laying too great stress on the duty of being conscious of the Spirit’s working within us, and in an odd insistence on the duty of exercising “faith in the indwelling Spirit” as the source of life—as if the Scriptures proclaimed the necessity of any other faith than that in Christ.

The Holy Spirit works through means (word and sacrament), something a Reformed minister ought to understand. Murray's stress upon "feeling the Spirit" at work within us, causes us to focus upon the inner life, not the external written word. This grounds the Christian life in subjective experience (emotions and feelings), and bypasses the hard work of sanctification in daily life--a work accomplished within us by the Holy Spirit even when we are not aware of his work (experientially). If pressed, Murray would be forced to base his argument for this in terms of his personal experience, because he could not do so from Scripture.

Warfield points out that Murray's phrase "faith in the indwelling Spirit" (focusing upon our experience of the Spirit's work) simply is not an expression found in Scripture. Nowhere does the Bible speak of faith "in the Spirit." Rather, the Bible repeatedly speaks of faith "in Christ" (and occasionally of faith "in God").

Another concern raised by Warfield is Murray's attempt to bifurcate the Christian life into an "entrance level" experience (coming to faith--regeneration) and a second level experience (the deeper level--sanctification), such as now commonly associated with the charismatic/Pentecostal notion of the Baptism of the Spirit as a second work of grace after initial regeneration.

Warfield identifies Murray's error in separating the Christian life into two parts (stages).

Here [Murray] introduces an undesirable dualism into the Christian life, finding two moments of development in it corresponding to the two objects of this twofold exercise of faith. He rightly modifies Mr. Boys’s statement as to the nature of prayer for the Spirit, and modifies it in the right direction; but it is a great pity that he adopts the confusion of the charismatic and gracious work of the Spirit upon which Mr. Mahan bases his separation of regeneration and sanctification. We must not separate these two works of the Spirit: it is no more true that whom God foreknew, them also he predestinated to be conformed to the image of his Son, and whom he predestinated, them also he called, and whom he called, them also he justified, than it is that whom he justified, them also he glorified, which surely includes more than external acceptance into the heavenly glory.

Warfield's concern is that the Bible knows nothing of a Christian stuck at the first level, and then missing out on the second level experience of a "higher life." God gives all his people all of his blessings through faith in Christ at the time of our conversion. There is no "second" level of experience, or a second work of grace which comes later.

The essence of this passage is to teach that God selects his children, chooses the goal to which he shall bring them, and brings them safely to that goal; and it justifies us in saying that without exception “whom he regenerates, them also he sanctifies.” The separation of these two begets the very evil which Mr. Murray deprecates, of failure to live up to our privileges.

Warfield cautions folk like Murray not to write before they read and process the work of others, a sin not limited to Rev. Murray, but one often committed in the current age.

Enthusiastic minds like Mr. Murray’s need to exercise special care in adopting forms of statement from other writers. We meet every now and then in the book with a phrase or a doctrine the implications of which have scarcely been thought through by him. For example, the crude trichotomistic anthropology of p. 34 is an excrescence [i.e., a disease or abnormality] on his thinking, and is adopted only to be laid aside. On p. 54 he speaks for a moment like a fully developed Schleiermacherite.

Two theological errors which result are here identified. The first is trichotomy--a widely held view then and now, which holds that humans are a tri-parite composite of body, soul, and spirit, and are not as Scripture teaches, a psychosomatic union of body and soul-spirit. The other error is that Murray unwittingly ends up with the same epistemology as the father of Protestant liberalism, Schleiermacher. Murray's careless expression implies that God cannot be known (i.e., there is no such thing as propositional revelation--Scripture), but can only be experienced through the feelings--the consequence of Murray's stress upon being conscious of the Spirit's present work within us.

Murray's lack of care in saying things in a biblically faithful, theologically sound, and logically coherent way frustrates the uber-careful Warfield. Murray's pen is far ahead of his mind when he writes.

And every now and then we strike against a sentence delivered as if it contained the very kernel of the Gospel, which quite puzzles us. For example, what idea of “holiness” underlies the assertion that “It is as the Indwelling One that God is Holy,” offered in defence of the statement that the Spirit is “the Holy Spirit” only as sent forth by the incarnate Christ? And what shall we do with the statement made in the same connection, “It is not the Spirit of God as such, but the Spirit of Jesus that could be sent to dwell in us,” in the face of the biblical usus loquendi?

Murray does not intend any heresy and does not openly teach it. But his strange and confusing formulations certainly open the door to such.

At the end of the day, Dr. Warfield is not very impressed with Rev. Murray's book, nor his proto-Pentecostalism.

The book is marred everywhere by such straining after novel and striking forms of statement, a vice, we may add, very common with books of this class.

The Presbyterian Review X, no. 37–40 (1889).

Sadly, books of this class and their common vices are still Christian bestsellers. We can only but wonder what the Lion of Princeton would have done with Joel Osteen or Joyce Meyer. Or with the Word-Faith folk who still love and read Andrew Murray?