Reid on Perception (Part Four)

Tuesday, August 14, 2018 at 11:07AM

Tuesday, August 14, 2018 at 11:07AM Reid on “Perception” -- Reid v. Kant and Van Til (Round One)

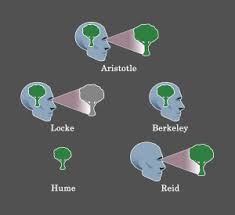

Kant argued that what we perceive with our senses is not “the thing in itself,” since sense data must be mediated through our a priori categories. We all may see the same object which exists independently of our minds. Yet, our experience of that object is mediated through our a priori categories, determining the outcome of our sensations. If I cannot be sure that what I and others see is the same thing, even if we are looking at the same object, does this not lead to some form of skepticism despite Kant’s objections to the contrary?

Kant argued that what we perceive with our senses is not “the thing in itself,” since sense data must be mediated through our a priori categories. We all may see the same object which exists independently of our minds. Yet, our experience of that object is mediated through our a priori categories, determining the outcome of our sensations. If I cannot be sure that what I and others see is the same thing, even if we are looking at the same object, does this not lead to some form of skepticism despite Kant’s objections to the contrary?

Our understanding of perception is especially important to keep in mind when thinking about the contemporary debate over apologetic method between “evidentialists” (who make appeal to “facts” of Christianity as objective and “true”) and “presuppositionalists,” (who believe that our a priori categories, in this case, belief in the God of the Bible, are all-determinative to the knowing process, so that it is something like a fool’s errand to attempt to argue for the truth of Christianity merely using facts). According to presuppositionalists, the best way to defend the faith is assume the truth of Christianity and challenge unbelievers on grounds of inconsistency, factual error, and personal prejudices.

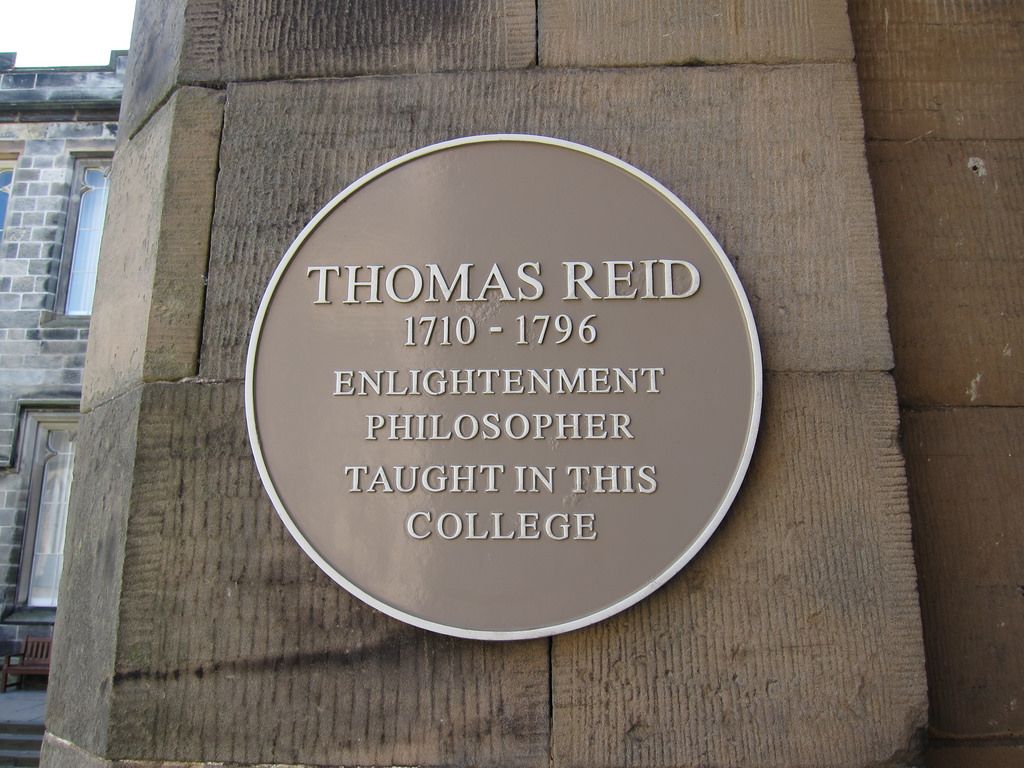

The founder of the modern school of presuppositionalism, Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) of Westminster Theological Seminary was “categorical” (pun intended) in his rejection of Kant’s absolute idealism and the latter’s distinction between noumenal and phenomenal realms (Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology, 103-115). But Van Til was greatly influenced by two Dutch Reformed theologians of an earlier generation, Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) and Herman Bavinck (1854-1921), both of whom utilized Kant’s a priori categories to explain how it is that we as fallen humans prejudicially (and sinfully) interpret the world around us–especially in light of the biblical data regarding the damage done to the human intellect and will by Adam’s fall into sin.

The traditional Reformed understanding of the effects of human sinfulness (including the so-called noetic effects of sin), when set forth through a priori categories such as Kant's, provided the ground for Abraham Kuyper to contend that the Fall completely effects the knowing process–so much so that Christians and non-Christians (through differing sets of a priori categories–one regenerate and one unregenerate) can properly be described as engaging in two kinds of science (note: you can insert any other human discipline here). There is a regenerate way of pursuing science, grounded in regenerate a priori categories, and there is an unregenerate way of doing science, grounded in sinful a priori categories. In this scheme, the gap between the way a Christian thinks and a non-Christian thinks amounts to a chasm. Van Til agreed and went so far as to state, “to the extent that the two systems of interpretation are self consistently expressed it will be an all-out global war between them” (Van Til, “Introduction” in Warfield, Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, 24).

This is also reflected in Van Til’s oft-repeated comments to the effect that it is useless to appeal to common ground or “common notions” upon which Christians (regenerate) and non-Christians (unregenerate) can both agree. God tells us (through Scripture) what things truly are and what they actually mean. In sense, this is where the discussion begins and ends for a regenerate person with regenerate a priori categories–they think God’s thoughts after him, while non-Christians cannot. This is why, according to Van Tilians, Christians should never appeal to non-Christians on the basis of facts supposedly held in common, when there cannot be any such thing. Instead, Christian apologetics ought to challenge non-Christian presuppositions while making the case that the world cannot make sense apart from Christian presuppositions and regenerate a priories. Christians and non-Christians will see the facts around them very differently (i.e., those things which occur in ordinary history in the external world in which we live) As Van Til puts it, “the only `proof’ of the Christian position is that unless its truth is presupposed there is no possibility of proving anything at all. The actual state of affairs as preached by Christianity is the necessary foundation of `proof’ itself” (Cornelius Van Til, My Credo, 21).

If true, this would be a vindication of Kant and present a serious challenge to Reid’s notion of first principles and common sense which make appeal not to regeneration and a priori categories, but to first principles and common sense which are universally held in common by believer and unbeliever alike even after Adam's fall. Here, we see the fundamental divide between two approaches to Christian apologetics within Reformed circles, evidentialism and presuppositionalism. There is good reason why someone like B. B. Warfield was thoroughly perplexed by Kuyper’s instance on two kinds of science (one regenerate, one not), along with with Kuyper’s and Bavinck’s depreciation of Christian evidences, such as Jesus’ resurrection, which make appeal to knowable and verifiable events of history (Warfield, “Review” of Bavinck’s De Zekherheid des Geloofs, 117). Warfield followed Reid, while Kuyper, Bavinck, and Van Til, followed Kant.

For Van Til, there can be no such thing as a “brute fact,” or “uninterpreted" fact. Van Til expressed great reservation about Reid’s view of perception in relation to facts. “In the case of Scottish Realism there is, to say the least, an undue emphasis given to the attempt to establish a realism or independence of the object over against the subject” (Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology, 132). In making this comment, Van Til openly sided with Kant over Reid.

But Van Til seems to be of two minds when it comes to Kant’s handling of "facts." While rejecting Kant’s system, Van Til clearly embraced Kant’s understanding of how we experience and know the external world–the subjective a priori categories are all-determinative. Van Til claims Kant’s “Copernican Revolution” provides “a fully consistent presentation of one system of interpretation over against the other. For the first time in history the stage is set for a head-on collision” (Van Til, “Introduction” Warfield, Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, 24). If Kant is right about the necessity of a priori categories determining the meaning of sensations coming from the external world, then facts and their interpretation are indeed one thing. With this notion, Van Til is in full agreement. What a Christian sees as evidence for Jesus’ resurrection, a non-Christian may see as evidence of a mythological tale invented by Jesus’ followers.

Perhaps talk show host-psychologist Dr. Phil provides a helpful illustration when he quips “perception is reality.” Dr. Phil says this of someone who is obviously misinterpreting and distorting reality. Exposing such is presumably the reason why such a person is a guest on his program in the first place. Dr. Phil has every hope, it seems, of convincing the troubled person that their misguided perception is not reality. If such perceptions are indeed ultimate, there would be no possibility of any further useful discussion. The only remaining option to provide any relief would be the prescribing of medication.

The very possibility of exposing ill-conceived perceptions is one hint that Van Til’s notion of facts and their interpretation being one is not so air-tight after all. What if Reid is right about how we perceive the world and that we must assume certain things to be true to even talk about the matter of how and why common sense works? Reality grounds perception–or ought to. For Reid, what is presupposed is not the entire content of the Christian faith, nor even the authority of Scripture–as it is for Van Til. What is presupposed by Reid is that all people think in a common way, and are able to do so because God made them with the ability to do so. Reid’s focus is on epistemological method grounded in human nature, not a priori categories or prior mental content.

So what does this have to do facts and their interpretation? To my knowledge, Reid never addressed this matter as we are doing here. Reid is not doing Christian apologetics, rather, he’s refuting Hume and writing before Kant. But I do think Reid would be very comfortable affirming that within the context of human life, certain things are “self-evident.” But facts are “self-evident” because they occur in a context–not as “brute facts.”

An analogy might be useful to flesh this point out a bit further. Consider the matter of interpreting facts as like attending a play. Suppose you were to walk in mid-play, say during act 7, scene 2. You witness a character speak, and then make an insulting gesture to another character. You then immediately walk out of the play. Even though you heard the words spoken and witnessed the gesture, you would have no idea of what the words or gesture means, nor why they were important to the story. No "brute facts" here.

But things are quite different if you watch the entire play. To get some context, before attending the play you might read several reviews, and you may even have done some research on the playwright. You also know in advance that some play-goers will interpret the characters or the story line differently than the playwright intended. But the play–specifically act 7, scene 2–would make much more sense to you, once you who know who the character is, and why his insult figures so prominently in the plot line of the larger story. You understand that you cannot infallibly interpret the play by reading the playwright’s notes, nor can you possibly understand why every character was present during particular scenes, or why they were given the particular lines they were. Yet, you would not need to do so, nor would you ever expect to do so, to enjoy the play which unfolds scene by scene, one scene building upon another. When you watch the play in its entirely, you can figure out what was going on, because you now have the context to understand what you saw in act 7, scene 2. So it is with facts–they always occur in a context.

This context is what Reid’s notion of common sense provides us. Facts never occur in isolation from other facts. There is always a context for our experience of the external world. In the case of Christ’s resurrection–the critical fact for any discussion of Christian apologetics–the context (i.e., the story line of the play) is the Old Testament’s prediction of the resurrection of the body at the end of the age, the Psalmist’s prophecy that the coming Messiah would not see decay, that his kingdom was everlasting, followed by Jesus’ appeal to the sign of Jonah when speaking on several occasions about how he would fulfill the predictions just mentioned.

Those Jews and the Romans who opposed Jesus’ messianic claims certainly were not regenerate (at least not yet for some of them), but they understood full well what Jesus’ resurrection meant, even if they never came to faith in Jesus and even if they denied that the resurrection ever happened. Granted, the Jews and Romans had vastly different presuppositions and interpretations of the resurrected Jesus than did Jesus’ followers post-resurrection. But the resurrection still stands as the supreme fact of Christianity. Rejection of Jesus’ resurrection as confirmation of his claims does not mean his resurrection never occurred. There was still an empty tomb, and Jesus continued to appear to his followers. The rejection of Jesus by unbelievers stemmed from sinful and willful prejudice (whether self-conscious or not)–what Paul describes as the suppression of truth in unrighteousness (Romans 1:18).

In this instance, we see the critical difference between Reid and Kant and how their differing understanding of perception impacts how we interpret “facts.” How do we perceive the world around us? Directly and spontaneously? Or is our perception of the world ultimately determined by our a priori mental categories? Or even through our sinful presuppositions? Reid, Kant, and Van Til offer quite different answers to these vexing questions.